Cost pressures are triggering project delays and cancellations: will they lead to new international arbitration claims?

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of GAR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

This article analyses recent international arbitration cases and potential drivers of cross-border disputes in the Americas. We review economic trends since the covid-19 pandemic and comment on the effects of these trends on the nature of future cases.

A striking economic trend for infrastructure projects is the immense cost pressure that developers face. The supply chain disruptions and high inflation that beset many infrastructure development projects during the covid-19 pandemic continue to have lingering effects and create a challenging environment for developers. For investments needed to effect the energy transition project, the scale of capital required is in the trillions of dollars. Managing these headwinds will be key to achieving the goals established under the Paris Agreement.

Challenges in completing new investment projects and questions about the extent to which the regulatory environment will protect investments in legacy fossil generation facilities have the potential to create new disputes in international arbitration. Rule changes, delays, cancellations and allegedly discriminatory treatment are likely causes for such disputes. Ongoing economic and financial volatility, persistently high inflation and continued high oil prices are likely to complicate the framing of cases and the calculation of quantum.

Discussion points

- Economic output remains weaker across the Americas

- Oil prices continue at above historical averages

- Inflation continues to exert pressure

- Developers face higher costs of capital

- Raw materials costs increase

- Infrastructure projects dominate arbitration disputes

- Energy transition project development fraught with delays and cancellations

- Volatile markets and the need for experts to parse effects unrelated to claims will continue to complicate quantum

Referenced in this article

- United States–Canada–Mexico Agreement

- Volga-Dnepr Airlines, LLC v Canada

- ADP International SA and Vinci Airports SAS v Chile

- WOM v Republic of Chile

- Grupo Energía Bogotá and Transportadora de Energía de Centroamérica v Guatemala

Economic output remains weaker across the Americas

After the initial effects of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020, world output (as measured by real gross domestic product (GDP)) rebounded in 2021. However, global recovery slowed substantially in 2022 and 2023 and was expected to remain weak in 2024, particularly in the Americas. Figure 1 shows the actual output growth for 2021, 2022 and 2023 and the forecast for 2024 for the world, advanced economies, emerging markets, the United States, Canada, and Latin America and the Caribbean.[1]

Figure 1. Actual and forecast growth by region and country

Notes and Sources: Data from IMF World Economic Outlook, published April 2024. 2024 forecast as of April 2024

As reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global output in 2021 increased by 6.1 per cent as many countries implemented expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to bolster their economic recovery and as covid-19 vaccines became widely available to the public.[2] However, following the robust rebound in 2021, the global recovery decelerated in 2022 and 2023, partly as a consequence of the war in Ukraine and headwinds from inflation.[3] Growth was expected to remain weak in 2024, given inflation rates, which, despite having fallen from their 2022–2023 highs, remain above the levels prevailing prior to the covid-19 pandemic.[4]

Oil prices continue at above historical averages

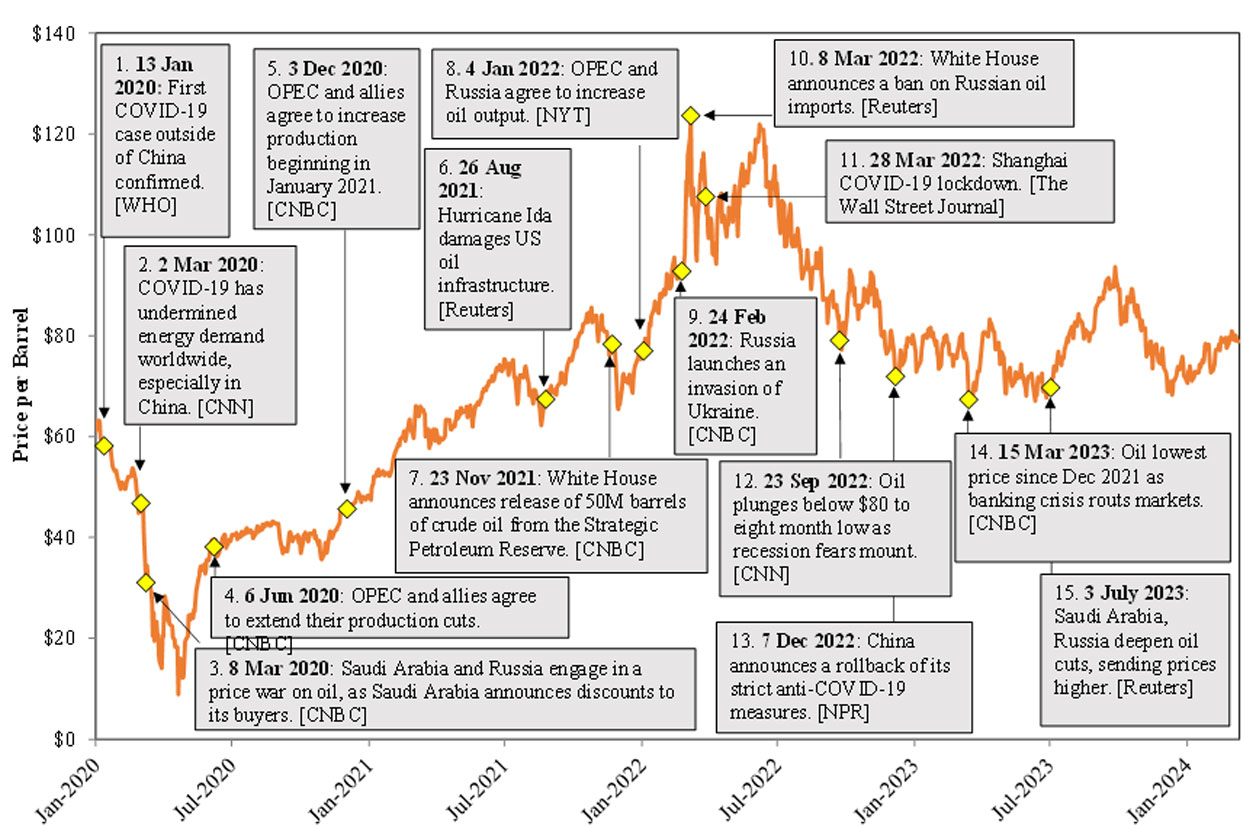

After a sustained period of growth and a peak triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, oil prices trended downwards in 2022 and early 2023. Since then, oil prices have stabilised at above historical averages. Figure 2 shows spot prices of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil, along with relevant key events, from January 2020 to early 2024.[5]

Figure 2. WTI crude oil spot prices and key events

Notes and Sources: Data from FactSet Research Systems, Inc Annotations from news articles obtained from Fuctia and Google WII price set to the previous day's price on 20 April 2020 to elanmate negative price on that day.

Similar to oil prices, natural gas prices increased rapidly from 2020 to mid-2022, followed by a highly volatile downward trend. In February 2021, natural gas spot prices exhibited extreme spikes during Winter Storm Uri on account of production disruptions and increased consumption.[6] Yet, apart from another price spike in January 2024, natural gas prices have decoupled from oil prices and remain relatively low. Figure 3 shows the spot prices for Henry Hub Natural Gas, along with relevant key events, from January 2020 to early 2024.[7]

Figure 3. Henry Hub natural gas spot prices

Because of the volatility in energy prices and continued high costs for oil and refined products, energy-intensive projects face cost pressure and uncertainty.

Inflation continues to exert pressure

In addition to higher oil prices, project developers face challenges due to the overall level of inflation in the economy, particularly with respect to wages and raw materials costs. For example, increases in the prices of raw materials have left turbine manufacturers struggling to maintain margins on existing contracts to deliver turbines, affecting the electricity generation sector and investments in new wind farms.[8] If margins erode even further, the contracts may end up being litigated.

Companies across the world face unusually steep cost increases resulting from inflation. Between 2007 and 2021, the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks aggressively printed money and acquired financial assets. Massive policy interventions during and after the global financial crisis greatly increased the balance sheets of major central banks. In response to the pandemic, central banks pursued additional expansionary measures that led to further increases in their balance sheet holdings. Since 2022, in response to the economy overheating and increasing inflation, the Federal Reserve and other central banks have pivoted to a contractionary policy and focused on reducing the size of their balance sheets.[9] Figure 4 shows the total assets of major central banks from 2007 to 2023. The general trend was upwards, spiking in 2020 and 2021, then declined as central banks shifted policy in 2022. The People’s Bank of China is the exception as it continues to grow its balance sheet, albeit modestly in the past few years.

Figure 4. Total assets of major central banks (2007–2023)

_1.gif?VersionId=MdR7HPuLAtJbnFq0WlmQqNiIrXVn6oFn)

Notes and Sources: Data from Bloomberg. Total assets as of December of each year.

Monetary expansion policies contributed to inflation climbing to levels not witnessed since the 1970s. Inflation in 2022 beat projections across the United States, Canada and Latin America. Inflation projections have been revised to even higher levels for the United States and Canada for 2024 and for Latin America until 2027. As shown in Figure 5, inflation in Latin America increased from 14 per cent in 2022 to 14.4 per cent in 2023 and was expected to increase further to 16.7 per cent in 2024. For the United States, inflation fell from 8 per cent in 2022 to 4.1 per cent in 2023 and was expected to fall further to 2.9 per cent in 2024. Similarly, in Canada, inflation slowed from 6.8 per cent in 2022 to 3.9 per cent in 2023 and was expected to slow further to 2.6 per cent in 2024.[10] Importantly, the IMF’s forecasts of inflation have increased in recent months, reflective of a lag between contractionary policies and the central banks’ ability to control inflation.

Figure 5. Inflation projections for the Americas (change in average consumer price index)

_1.gif?VersionId=esRwiLF33n5hqqhZbQZdCkVniR1SlBvp)

Notes and Sources: Data from IMF World Economic Outlook Database, published April 2024

Developers of infrastructure projects have also confronted major increases in raw materials costs. As shown in Figure 6, metals costs, in particular, have exhibited considerable volatility while following a general upward trend. Costs for some raw materials appear to be levelling off, though others continue to increase.

Figure 6. Indexed prices of select commodities and products

Notes and Sources: Data from Bloomberg LP, and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Developers face higher costs of capital

Since we last wrote about economic conditions,[11] we have observed a key shift in the investment climate. Contractionary central bank policies have included higher lending rates; correspondingly, long-term government bond yields have doubled and, in some cases, tripled. Since government bond yields are the baseline over which credit spreads are applied to arrive at a given firm’s cost of borrowing, their increase has had a profound effect on the cost of capital for infrastructure project development.

Figure 7. Government bond yields in Latin America relative to global benchmarks

Notes and Sources:Data from Refinitiv and FRED.

Infrastructure projects dominate arbitration disputes

Many significant disputes involving parties from the Americas are resolved through international arbitration. For example, a review of publications from Global Arbitration Review and Law360 on international arbitration cases in the Americas indicates that, from September 2020 until early 2024, more than 200 international arbitration proceedings involving at least one party from the Americas were commenced.[12] Since many commercial arbitrations are confidential, these figures do not encompass all arbitration proceedings initiated over this period. The manufacturing, construction, infrastructure and transportation sectors account for the majority of disputes, at 22 per cent of cases. The energy and mining sectors each account for 20 per cent of cases, while the finance, insurance and real estate sectors make up 12 per cent of cases and the information and communications sector 7 per cent. Cryptocurrency accounts for 1 per cent of cases, with the remaining percentages pertaining to other industries.

Figure 8. Count of damages and international arbitration cases in Americas by sector, 2020 to early 2024

Notes and Sources: Based on articles from Global Arbitration Review and Law 360 on international arbitration cases in the Americas. "Other" includes services and trade, fishing and forestry, agriculture, pharmaceutical, intellectual property, administrative, entertainment, food and beverage, tobacco, waste management, and water supply.

We note that the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation created a hotbed for investor-state disputes, including disputes involving the Americas, as several countries imposed sanctions on Russia at an unprecedented scale and scope. Volga-Dnepr Airlines, LLC v Canada provides an example.

The Canadian government seized a Volga-Dnepr cargo aircraft at Toronto Pearson International Airport in February 2022. After unloading its cargo, the aircraft was banned from departing due to Canadian authorities’ ban on the use of Canadian airspace by Russia-operated aircraft imposed in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In June 2023, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Volga-Dnepr’s confiscated aircraft would be moved to Ukraine to assist the war effort. Volga-Dnepr said that it would initiate arbitration under the bilateral investment treaty if the dispute was not resolved within six months but ‘remains open to negotiations with Canadian representatives to resolve the issue and return the aircraft’.[13]

Looking ahead, the volume and nature of arbitration in the Americas may continue to focus on capital-intensive infrastructure and energy projects, since those projects are most affected by the changing investment climate, and the ability to perform on contracts struck in a different economic environment is likely to continue to present delays, attempts at renegotiation and even project cancellation.

Energy transition project development fraught with delays and cancellations

The energy transition project is the most capital-intensive public policy initiative in our lifetimes. We review recent experiences with energy transition investments in the United States, Canada and Latin America in turn.

In the United States, energy transition investments are in full development at all levels. Favourable tax treatment and local utility incentives encourage the development of behind-the-meter rooftop solar and battery storage at residences and businesses. For utility-scale projects, independent power producers and regulated utilities advance all types of low-carbon generation, including hydro, geothermal, onshore and offshore wind, solar and storage. Most states have implemented renewable portfolio standards, which require sellers of electric energy at retail to source a minimum percentage of their power from renewable resources.

US President Joe Biden joined with other nations in committing to meet the goals outlined in the Paris Agreement. A key to meeting these goals is the creation of an offshore wind industry. President Biden announced a ‘30-gigawatt-by-2030’ national offshore wind energy goal. Individual US states are procuring contracts to facilitate the construction of thousands of megawatts of new offshore wind capacity, yet the commercial operation dates for some facilities have been pushed back or cancelled due to various supply chain constraints, higher interest rates raising financing costs, and litigation in US courts relating to the effects of the new facilities on the local environment and communities.

The industry is fraught with challenges as the cost to construct offshore wind turbines has skyrocketed, though at least certain elements of pricing were determined before the rise in costs. David Hardy, group executive vice president and chief executive officer of the Americas at Ørsted, explains: ‘Macroeconomic factors have changed dramatically over a short period of time, with high inflation, rising interest rates, and supply chain bottlenecks impacting our long-term capital investments. As a result, we have no choice but to cease development of Ocean Wind 1 and Ocean Wind 2.’ SNL Energy reports that about ‘one-third of the total offshore wind capacity contracted on state-sanctioned procurements to date is now in dispute’.[14]

So far, one path that developers have taken is simply to pay a penalty for terminating the contract early. ‘The current [power purchase agreements] are not economic, in light of significant and unforeseen inflation, supply chain and financing cost increases affecting the US offshore wind industry’, said SouthCoast Wind in cancelling its contract with a penalty of US$60 million.

Although the offtake contracts for offshore wind in the United States do not provide for arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism,[15] the cost pressures and inability to perform at contracted prices may be a harbinger for cases elsewhere in the Americas and potentially for commercial disputes in international arbitration tied to projects in the United States. After all, the projects typically involve international investors contracting across a global supply chain and, as such, frequently confront issues of international law. Time will tell which parties are able to resolve the disputes amicably and which will raise new claims before international tribunals.

Table 1 presents the status of a subset of the offshore wind projects under development in the north-eastern United States.

Table 1. Status of select offshore wind projects in New England and the United States mid-Atlantic

| Project | State | MW | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revolution Wind | Connecticut | 704MW | Planned operation date pushed back from 2025 to 2026[16] |

| Skipjack Wind | Maryland | 966MW | Agreement with Maryland withdrawn, developer seeking a new PPA[17] |

| Ocean Wind 1 | New Jersey | 1,100MW | Project cancelled[18] |

| Ocean Wind 2 | New Jersey | 1,148MW | Project cancelled[19] |

| South Fork Wind | New York | 132MW | Operational[20] |

Sunrise Wind | New York | 924MW | Projects rebid with a significantly higher all-in development cost (US$83.36/MWh to US$150.15/MWh)[21] |

| Empire Wind 1 | New York | 810MW | Projects rebid with a significantly higher all-in development cost (US$83.36/MWh to US$150.15/MWh) |

| Empire Wind 2 | New York | 1,260MW | Contract cancelled[22] |

| Beacon Wind 1 | New York | 1,230MW | Renegotiation request on contract denied[23] and ownership shift |

| Beacon Wind 2 | New York | 1,170MW | Renegotiation request on contract denied[24] and ownership shift |

| SouthCoast Wind | Massachusetts | 2,400MW | Paying US$60 million penalty to break contract[25] |

| Commonwealth Wind | Massachusetts | 1,080MW | Paying US$48 million penalty to break contract[26] |

| Park City Wind | Massachusetts | 791MW | Paying US$16 million penalty to break contract[27] |

| Leading Light Wind | New Jersey | 2,400MW | Construction paused due to difficulty finding manufacturer for turbine blades[28] |

Canada has also committed to meet emissions reduction targets set forth in the Paris Agreement, setting the stage for massive new investments in energy transition infrastructure. Canada needs to invest C$2 trillion between now and 2050 to meet these goals.[29]At the provincial level, the targets can require swifter movement, as indicated in Table 2.

Table 2. Emissions reductions policies by Canadian province

| Province | Description |

|---|---|

| Alberta | Annual cap of 100 megatonnes (MT) on oil sands emissions and a target for reducing methane emissions from upstream sources 45% below 2014 levels by 2025. Obtain carbon neutrality by 2050.[30] |

| British Columbia | Increase the use of clean and renewable energy and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80% by 2050.[31] Phased decrease: 40% below 2007 levels by 2030, 60% below 2007 levels by 2040, and 80% below 2007 levels by 2050. |

| Manitoba | Poised to achieve its first GHG emissions target of 1MT for the period 2018–2022 and to set a new cumulative GHG emissions reduction goal of not less than 5.6MT over the next five years. Zero GHG emissions by 2050.[32] |

| New Brunswick | Phase out coal by 2030 and achieve net zero electricity supply by 2035.[33] Net zero GHG by 2050.[34] |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Reduce provincial GHG emissions by 30% below 2005 levels.[35] |

| Nova Scotia | Reduce GHG emissions by 53% below 2005 levels by the year 2030. Net zero by 2050.[36] |

| Ontario | Reduce GHG emissions by 80% below 1990 levels by 2050, with two mid-term targets: 15% below 1990 levels by 2020 and 37% below 1990 levels by 2030.[37] |

| Prince Edward Island | Net zero by 2040.[38] Aims to be the first province in Canada to be net zero. |

| Quebec | Reduce GHG emissions by 37.5% from 1990 levels by 2030 and become carbon neutral by 2050 by electrifying the economy.[39] |

| Saskatchewan | Reach net zero GHG emissions by 2050, or earlier, and maintain a 2030 GHG emissions reduction target of 50% below 2005 levels by 2030.[40] |

A hiccup in the Canadian transition, however, has been a moratorium imposed by the Albertan government at the provincial level. Alberta’s United Conservative government announced in September 2023 that the province’s utilities commission would pause all approvals for large renewable energy projects for six months, ending February 2024. The moratorium affected all solar and wind projects greater than 1MW. The province said that it was responding to concerns about the developments’ impact on agricultural land, reclamation and the reliability of the power source. It is estimated that over 100 projects, worth more than C$33 billion, were put on hold during the moratorium.

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), most countries have committed to the emissions reduction targets established in the Paris Agreement in November 2016. Among the 196 parties that signed the agreement are Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Columbia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay and Venezuela.

The Paris Agreement’s overall goal is to hold ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’ and pursue efforts ‘to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’. To keep global warming to no more than 1.5°C, emissions need to be reduced by 45 per cent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050.[41]

To achieve the ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement requires a substantial increase in energy investments. Investments in clean energy need a major boost – significantly above current investment levels – to reach energy-related emissions reductions goals. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy investments in Latin America must increase by almost 80 per cent, requiring an increase in spending to 4.1 per cent of the region’s GDP. The dollar investments required are staggering, with almost US$1 trillion in LAC investment required between 2026 and 2030 just for the energy sector, or US$180 billion per year.[42]

One of the most critical barriers for the financial viability of energy projects in the region remains the region’s high cost of capital. For example, in 2021, the cost of capital for a typical solar photovoltaic (PV) plant in Brazil was between 12.5 per cent and 13.5 per cent, among the highest compared with other emerging economies.[43] The cost of capital in Mexico was likewise in the range of 9.5 per cent to 10 per cent. According to the IEA Cost of Capital Observatory, the cost of capital in Brazil and Mexico was two-to-three-times higher than in China, Europe and the United States during that same period.[44]

This high cost of capital is driven by the assessment of country- and project-specific risks. Long-term government bond yields can provide an indicator of investors’ requirements for taking on the risks of investing in a given country. As can be seen in Figure 7, the government bond yields of LAC countries are generally higher than other benchmarks. Higher interest rates make it challenging for the region to obtain funding for projects. This is a key concern in the region, as the energy transition requires a lot of investment in assets such as solar PV and wind, which rely heavily on debt.[45]

Finally, permitting, licensing and approval processes can delay the start of projects or hinder their execution. Numerous investor-state disputes have focused on impediments to permitting and other government approvals. Before the pandemic, local communities opposed many large projects and engaged in tactics such as road blockades. In other cases that ended up in litigation, government bodies allegedly acted prejudicially against project developers, for example by denying permits, which impedes their ability to carry out necessary investments. Such disputes are likely to continue.

One example is the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes’ claim that Grupo Energía de Bogotá and its Guatemalan subsidiary Trecsa launched against Guatemala for multiple delays in the deployment of its power grid. The two companies are claiming US$403 million plus interest in damages. They allege that the delays are attributable to Guatemala, which, they say, failed to provide necessary support and permits at the national and municipal levels. They also claim that court rulings were issued, paralysing the project in specific locations pending local consultations that the state should have already carried out.[46]

Volatile markets and the need for experts to parse effects unrelated to claims will continue to complicate quantum

To the extent that damages that go beyond contractually stipulated delay amounts can be claimed, the analyses will require thoughtful and careful work to construct reasonable but-for assumptions. As noted, cost increases derive from a variety of factors ranging from the ground war in Europe to central bank policies to supply chain constraints. While it is difficult to predict the specific nature of any given claim, it is clear that isolating a quantum of damages directly tied to a set of alleged acts will require experts to parse the effects of various economic drivers.

The authors would like to thank their NERA colleagues Benjamin Tello and Juliette Min for research assistance and Willis Geffert for useful comments.

Endnotes

[1] ‘World Economic Outlook, April 2024’, International Monetary Fund.

[2] ‘Global economic recovery continues but remains uneven, says OECD’, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 21 September 2021.

[3] ‘Multiple crises unleash one of the lowest global economic outputs in recent decades, says UN report’, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 25 January 2023.

[4] ‘Regional Economic Outlook: The Western Hemisphere’, International Monetary Fund, April 2023.

[5] West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil price data from FactSet Research Systems, Inc. The WTI price serves as a benchmark for the pricing of US crude oil. See, for example, ‘Oklahoma’, US Energy Information Administration, available at https://www.eia.gov/state/index.php?sid=OK.

[6] ‘U.S. natural gas prices spiked in February 2021, then generally increased through October’, US Energy Information Administration, 6 January 2022.

[7] Henry Hub spot price data from Bloomberg, LP. Natural gas spot prices set at Henry Hub serve as the benchmark for the pricing of North American natural gas prices. See, for example, ‘Henry Hub Emerges as Global Natural Gas Benchmark’, Dow Jones Institutional News, 17 August 2017.

[8] See ‘Siemens Energy’s struggling wind unit blows Germany’s largest spinout off course’, Financial Times, 24 February 2022.

[9] ‘Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet’, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 4 May 2022.

[10] Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, published April 2024.

[11] See Jorge Baez, Kurt G Strunk and Robert Patton, ‘Damages: Geopolitics increases caseloads and complicates quantum’, Global Arbitration Review, 2022.

[12] Note, this is a general review of relevant GAR and Law360 publications rather than a comprehensive review of all international arbitration disputes in the Americas.

[13] Tom Jones, ‘Russian airline threatens treaty claim against Canada’, Global Arbitration Review, 15 August 2023.

[14] SNL Energy, citing ClearView Energy Partners: ‘Offshore wind contract disputes proliferate as high costs jeopardize US buildout’, 16 June 2023.

[15] For example, the NYSERDA OREC draft contract called for disputes to be heard in a court of competent jurisdiction of the State of New York.

[16] Alex Kuffner, ‘What’s happening with the Revolution Wind project? Here’s where it stands.’, The Providence Journal, 16 August 2024.

[17] Mike Smith, ‘Skipjack Wind bowing out of Maryland offshore wind deal’, Coastal Point, 1 February 2024.

[18] Diana Furchtgott-Roth, ‘Gone with the wind: Cancellation of offshore turbine project a boon for New Jersey’, The Heritage Foundation, 14 November 2023.

[19] ibid.

[20] ‘Governor Hochul announces South Fork Wind delivers first offshore wind power to Long Island’, New York State, 6 December 2023.

[21] The all-in development cost is a weighted average between the winning bids for Sunrise Wind and Empire Wind 1.

[22] Keith Goldberg, ‘Equinor, BP scrap offshore wind farm deal with NY’, Law360, 3 January 2024.

[23] Maria Gallucci, ‘Two major New York offshore wind projects are back on track’, Canary Media, 29 February 2024.

[24] ibid.

[25] Chris Lisinski, ‘2nd wind developer moves to terminate its contracts off Martha’s Vineyard’, NBC Boston, 30 August 2023. See alsoHeather Richards, ‘Offshore wind is at a crossroads. Here’s what you need to know’, E&E News by Politico, 13 November 2023.

[26] Jenette Barnes, ‘Avangrid’s Commonwealth Wind to pay $48 million penalty to terminate offshore wind contracts’, CAI, 20 July 2023.

[27] Brendan Crowley, ‘Avangrid cancels Park City wind contract, pays state $16M penalty’, CT Examiner, 3 October 2023.

[28] ‘NJ hits pause on offshore wind farm that can’t find turbine blades’, New Jersey 101.5, Associated Press, 25 September 2024.

[29] Cynthia Leach, ‘Financing greener growth: The fall economic statement needs to accelerate green investment’, RBC Special Reports, 1 November 2022.

[30] Alberta, ‘Emissions Reduction and Energy Development Plan’.

[31] British Columbia Utilities Commission, ‘BC’s Energy Transition’.

[32] Climate Action Team, ‘Manitoba’s Road to Resilience’.

[33] Nuclear Engineering International, ‘New Brunswick releases energy strategy’.

[34] Naius Research, ‘Pathways to net zero greenhouse gas emissions in New Brunswick’.

[35] Newfoundland and Labrador, ‘The Way Forward, On Climate Change in Newfoundland and Labrador’.

[36] Climate Change Nova Scotia, ‘What Nova Scotia Is Doing’.

[37] Ontario, ‘Ontario’s Climate Change Strategy’.

[38] Prince Edward Island Canada, ‘Greenhouse Gas Emissions’.

[39] Quebec.ca, ‘Quebec’s commitments in respect of the climate’.

[40] SaskPower, Our Power Future, Creating a Cleaner Power Future, ‘Emissions’.

[41] United Nations, Climate Action, ‘For a livable climate: Net-zero commitments must be backed by credible action’.

[42] International Energy Agency, Latin America Energy Outlook, November 2023, p. 164.

[43] id., p. 35.

[44] ibid.

[45] ibid., p. 35.

[46] Cosmo Sanderson, ‘Guatemalan power project generates ICSID claim’, Global Arbitration Review, 5 November 2020.