Valuation approaches in telecoms arbitrations: commercial arbitrations

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of GAR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

The fundamental objective of every damage assessment in commercial arbitrations is to put the injured party in the same economic position it would have been in but for the wrongful act.[2] Damages can rarely be quantified by observation or a readily available analysis. Thus, most often, damages are calculated as the difference of two values as at the same valuation date – one ‘as expected/warranted’, assuming the wrongful act had not occurred, and one ‘as is’ value.[3] This valuation approach is also considered the ‘differential method’, applying the widespread ‘but for’ theory in damages calculation.

In commercial arbitrations in the telecommunications industry, several valuation methods are used in practice. Since different valuation approaches may lead to (slightly) different results, the appropriate valuation method or methods should be selected carefully depending on the characteristics of the respective case.

Thus, the following sections briefly illustrate the basic valuation concepts and provide a short introduction to valuation approaches and methods most often applied in commercial arbitrations in the telecommunications industry according to our experience in this industry over decades.

The valuation approaches introduced hereafter primarily focus on disputes between telecommunications providers that are resolved through commercial arbitration. Dispute resolution mechanisms applicable to conflicts with regulators or government ministries are not addressed, although the damage methodology might be largely similar.[4]

Valuation approaches

Depending on the circumstances of the specific case and the assumptions taken, the values determined by different quantum experts most often diverge. Therefore, experts and arbitrators alike are often confronted with value ranges. Then, they must decide which valuation approach is the most appropriate in the specific case or what weight to attribute to different methods and assumptions presented.

There is not one valuation approach that is suitable for every possible situation. Rather, the most appropriate method must be selected based on the specifics of the case and the available information. According to the International Valuation Standards, which form a foundation of international valuation best practices often equally applicable to damage assessments, three principal valuation approaches are used in valuations:

- a market approach (e.g., comparable publicly traded companies method or comparable transactions method);

- an income approach (e.g., discounted cash flow (DCF) method); and

- a cost approach (e.g., net asset value or sunk costs).[5]

Each of these principal valuation approaches comprises different methods of application in commercial arbitrations. In the following sections, we briefly summarise the peculiarities of the three valuation approaches applicable to telecoms arbitrations in more detail.

Market approach

The market approach is a relative valuation approach and rests on the premise that comparable assets should have comparable prices. Consequently, the market approach uses observable market prices of comparable assets to determine the value of the asset to be valued. In simplified terms, it applies the rule of three, that is to say, the price observable for a similar asset is compared with the asset in dispute.[6] It requires that there is a sufficient number of observable market prices for the specific asset to be valued. Moreover, it assumes that the observable market price of an asset reflects its (market) value.

Market prices can be obtained either from recent transactions of comparable assets around the valuation date (comparable transactions method) or from contemporaneous (share) price quotes (publicly traded companies method).[7]

The search for a benchmark is usually based on telecommunications companies, contracts or assets operating in the same geographical region as the valuation subject and sharing similar characteristics, such as profit margins, risk profile and growth.[8]

This leads to the limitation of the market approach often observable with telecommunications companies. When valuing a disputed telecommunications company, contract or asset, more often than not, no perfectly comparable valuation subjects are available around the valuation date. In particular, telecommunications contracts and assets are often very specific and hardly comparable with other contracts or assets for which market prices are known.

Consequently, the market approach is most often limited to an application with entire companies, such as in post-M&A disputes of telecommunications companies. In such a setting, an entire telecommunications company might be evaluated, which offers the possibility to refer to a group of (stocklisted) companies or recent company transactions (peer group) that are reasonably comparable.

The selection of the peer group, however, is often contested between opposing quantum experts. It is a subjective assessment of each quantum expert which companies are considered comparable and how many companies should be included in the peer group to have a sufficiently large population.

The simplicity of the market approach is both a blessing and a curse. The results of a multiple-based valuation are easy to understand and require fewer assumptions than other valuation approaches. The damages calculation usually fits on a sheet of paper. However, the multiple-based valuation can be distorted, for example if there is insufficient comparability between the benchmark and the valuation subject.

Thus, when applying the market approach to determine damages, the expert should act carefully. Often, it may seem advisable to supplement the market approach by other valuation methodologies.

Income approach

The income approach determines the value of a company, contract or asset as the net present value of its expected future cash flows, applying a discount rate that reflects the time value of money and the risk attributable to these cash flows.[9]

The predominant form of the income approach is the DCF method, which is widely used in all kinds of valuation settings.[10] The reason for the success of the DCF method is quite simple. It provides great flexibility and can be applied to almost all businesses, contracts and assets that are generally profitable and where the business is generally profit-oriented.[11] Given that most telecommunications arbitrations involve profit-oriented companies, the income approach is frequently used to assess all kinds of damages relating to telecommunications companies, contracts or assets.

Conceptually, the present values of the expected future cash flows are derived by discounting the cash flows (in the numerator) to a reference date, allowing for a specified discount rate (in the denominator), as illustrated in the following formula:

The cash flows are made comparable with how the financial markets would price such cash flows.

The most important rule in the above formula is that the denominator and the numerator must match in terms of currency, maturity, taxation and risks (equivalence principle). However, in the practice of damages assessments, the equivalence principle is often violated. This leads to an over- or underestimation of damages. Frequently observable examples violating the equivalence principle comprise: (1) discounting cash flows denominated in a certain currency (e.g., the Brazilan real) with a discount rate that is derived from inputs denominated in a different currency (e.g., US dollar); (2) discounting long-term cash flows (e.g., cash flows from a contract with a 20-year term) with short-term discount rates (e.g., risk-free rate based on five-year government bonds) or vice versa; and (3) double counting of risk in the cash flow (e.g., reducing the estimated cash flows for a perceived risk) and again in the discount rate (e.g., adding a risk premium for the same perceived risk). It often becomes difficult to identify the different deficiencies for the arbitral tribunal.

The key steps when performing a DCF valuation-based damages assessment can be defined as follows:

- choose the most suitable cash flow type for the nature of the business, contract or asset in dispute (e.g., considering the data availability and real or nominal cash flows);

- determine the relevant valuation date, the appropriate valuation period and the valuation intervals (e.g., monthly, quarterly or yearly cash flows);

- if the damages period is not limited, determine whether the consideration of a terminal value (based on a sustainable level of cash flows) is appropriate;

- derive the cash flows relevant for the determination of damages, either:

- as the difference of cash flows expected ‘but for’ the damaging event during the valuation period and the expected cash flows ‘as is’ for the same period; or

- by directly assessing the cash flows from the wrongful act;

- determine the appropriate discount rate under consideration of the above-mentioned equivalence principle; and

- apply the discount rate to the expected cash flows and terminal value, if any.

We discuss the most relevant input parameters required for such an income approach in the following sections.

Estimating cash flows

The cash flows applicable in the income approach can be either (free) cash flows or (incremental) profits. Before estimating (future) cash flows, an analysis should be made of historical revenues, costs, investment levels and growth rates, etc. Additionally, market reports provide valuable and neutral (benchmark) information to evaluate financial developments in the past and in the future. If the projection of cash flows deviates from the expectation of the general market development or historical levels, the assumptions leading to major deviations should be explained and documented. In general, the business plan must appear reasonable and aligned with the underlying strategy or purpose of the company, contract or asset.

What is often more disputed, however, is the duration of cash flows. When calculating damages in commercial telecommunications arbitrations applying the DCF approach, the duration of the period in which losses are incurred needs to be considered.

Normally, the loss period begins with the date of the wrongful act. However, the end of the loss period can vary. Accordingly, the damages amount derived is directly affected by the length of the damage period assumed. Generally, the longer the damage period, the higher the damages. The specific duration of the damage period usually depends on the valuation subject.

If the wrongful act permanently impairs the profit-generating abilities of the harmed company, the loss period is often unlimited. This practice is in line with the valuation of businesses where an infinite lifetime is generally assumed.[12] In this situation, a two-stage DCF model is used most often.[13] The first stage comprises the explicit forecast period, and the second stage, which is often referred to as the ‘terminal value’, assumes that the cash flows will grow at a constant perpetual growth rate.[14]

For cases involving a telecommunications contract or asset, the damage period is usually limited. It most often represents the (remaining) term of the agreement or the asset lifetime in dispute. Renewal options and prolongations must be considered according to the individual circumstances and the likelihood of such terms.

Deriving the discount rate

As indicated before, the discount rate is meant to represent an alternative investment with characteristics that are comparable with the valuation subject regarding maturity, financial risk, operating risk, including currency risk and taxes.[15] Consequently, the value of cash flows occurring at different times can be assessed and compared only because of the discount rate making the cash flows comparable.

The discount rate neutralises the uncertainty inherent in the future cash flows as well as the time value of money. Future cash flows cannot be forecast with certainty since the future itself is uncertain.

The discount rate usually comprises several parameters,[16] each of which must be determined to best reflect the equivalence principle as at the valuation date.

Perpetual growth rate

As mentioned above, a perpetual growth rate is applied in cases where the wrongful act permanently impairs the profit-generating abilities of the harmed telecommunications company. It can be another major driver for damages.

The perpetual growth rate considered in the terminal value calculation has the same effect as the extrapolation of the cash flows with a certain average annual growth. This is a pragmatic shortcut to avoid the modelling of an unreasonably long damage period. Financially, it represents the growth in volume, prices or inflation over time.

Premiums and discounts

Although the cash flows and the discount rate should generally capture all impacts of the value of a business, there might be situations where the consideration of certain premiums or discounts might be applicable.

In this context, the International Valuation Standards emphasise that:

When using an income approach it may also be necessary to make adjustments to the valuation to reflect matters that are not captured in either the cash flow forecasts or the discount rate adopted. Examples may include adjustments for the marketability of the interest being valued or whether the interest being valued is a controlling or non-controlling interest in the business.[17]

Hereafter, we briefly discuss the concepts of an illiquidity discount and the application of a control premium.

Illiquidity discount

When valuing a telecommunications company or asset, the extent to which the asset is liquid[18] or marketable might be considered. Market liquidity risk relates to the inability of trading at a fair price with immediacy.[19] Liquidity in a market means that an asset can be sold rapidly, with minimum transaction costs and at a competitive price.[20] Consequently, an illiquidity discount would theoretically apply to assets that are neither listed at an organised exchange nor actively traded in an over-the-counter market. This understanding is also confirmed by economic research: ‘Both the theory and the empirical evidence suggest that illiquidity matters and that investors attach a lower price to assets that are more illiquid than to otherwise similar assets that are liquid.’[21]

However, determining an adequate size of an illiquidity discount is challenging in most cases and thus often highly controversial. Illiquidity discount studies exist for both minority and majority interest, but their informative value must be critically questioned.[22]

Studies on illiquidity discounts for majority interest analyse differences in transaction multiples between private and publicly listed companies. As explained in the ‘Market approach’ section, above, multiples can be distorted, which might also lead to distorted results from the studies.

Illiquidity discounts for minority interest can be observed in either (1) restricted stock studies that compare stock prices of listed companies with prices paid in private placements or (2) studies based on initial public offerings (IPOs) that compare the value of minority shares with prices paid on average in IPOs. However, before considering the application of illiquidity discounts found in such studies, the inherent selection bias and potential other biases should be carefully reviewed.[23]

The question of whether such a discount should be considered in a commercial telecommunications arbitration is always dependent on the circumstances of the specific case. If there is the need to consider an illiquidity discount, it usually must be calculated both for determining the ‘but for’ market value of the asset in dispute without the wrongful act as well as in calculating the ‘actual’ market value resulting because of the wrongful act.

This applies even more to situations in which the dispute relates not to equity shares but to tangible or intangible assets. In such cases, there is typically no or only very limited relevant market data available, so the determination of an applicable illiquidity discount is predominantly based on the quantum expert’s subjective assessment.

Control premiums and discounts for lack of control

In commercial telecommunications arbitrations, control premiums or discounts for a lack of control typically play a less prominent role compared with discounts for illiquidity. Nonetheless, if they are applied, they are often used incorrectly.

When valuing a minority or non-controlling interest, the minority shareholder is typically exposed to the risk of (1) an inefficient management of the company or (2) deliberately unfavourable treatment by the controlling shareholders. Therefore, the value of controlling a firm lies in the theoretical opportunity to run a company more efficiently than the current decisive shareholders, which would increase the performance of the firm and hence the owner-specific cash flows compared with the status quo. ‘Consequently, the value of control will be greater for poorly managed firms than well run ones.’[24]

Generally, the appropriateness of a control premium or a discount for the lack of control depends on the underlying valuation basis. When deciding whether a control premium or a discount for the lack of control is appropriate, whether the underlying business plan assumptions of the damage calculation includes (explicitly or implicitly) the premise of having control of a business needs to be analysed. In such cases, a further consideration of a control premium might be misleading.

In practice, the quantification of control premiums or discounts for lack of control often leads to controversies. Theoretically, they should be calculated based on the cash flows directly attributable to control. However, quantum experts in practice often rely on studies that compare total acquisition prices paid for controlling interests in publicly traded securities with the respective prices before such a transaction was announced. Examples can be found in studies such as MergerStat. However, ‘control premium studies’ should be assessed critically when specifically determining the value of control.[25] Each transaction included in these studies may have specific factors that affect its pricing. Therefore, a quantum expert needs to critically examine the case at hand before drawing a conclusion about the size of a potentially applicable control premium – if it is applicable.

Cost approach

In commercial telecommunications arbitrations, the cost approach is often applied to determine what a claimant has already spent, namely sunk costs. In general, the cost approach is based on the premise that an investor will not pay more for a telecommunications company, contract or asset than the cost to purchase or construct a company, contract or asset of equal utility.[26]

However, the value of a company, contract or asset is usually higher than the sum of the individual investments made in the past or to be made as at the valuation date. This is due, for example, to the company’s intellectual property, its existing customer base, its brand, its know-how on the efficient use of its assets and its profit-generating ability. No profit-oriented investor will, for example, spend US$1 billion to build a telecommunications network to receive only US$1 billion from this network in the future. Consequently, when a company regularly generates income streams and is realising an adequate return on its assets, the cost approach is usually not making a claimant whole. The cost approach may underestimate damages.

In any event, there are circumstances where the cost approach is useful.

First, the cost approach is an important tool to determine the fair value of a valuation subject if (1) the subject does not produce a (separable) income stream, (2) a business plan cannot be determined or (3) market data of comparable assets is not available.

Second and furthermore, the cost approach can be applied to calculate a floor value for a valuation subject in a hypothetical liquidation setting. This assumes that an owner would not continue to operate the business or asset if the owner can realise a higher return by breaking up and selling the business or asset. This floor value is also the floor for damages.

In any event, the cost approach is (still) applied by arbitration tribunals, given that it leaves less room for discretion of the quantum experts and is easier to verify.

Selection of an appropriate valuation approach

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the most appropriate valuation method must be selected based on the specifics of the case and the available information.

Although a study of awards in commercial International Chamber of Commerce arbitrations found that the valuation methodology most often relied on was the cost approach, during the past decade, we have observed a trend towards the market and income approaches.[27]

The income approach usually offers the greatest flexibility for commercial telecommunications arbitrations. Also, mitigation factors can be comprehensibly included in the damages calculation under the income approach.[28]

Many commercial disputes in the telecommunications industry relate to licensing and supply agreements, M&A transactions or patents. In such cases, the subject in dispute is most often unique, and market prices of comparable assets hence are not available. The cost approach, on the other hand, might not be suitable to determine damages, as the costs incurred (or avoided) by the damaging party often are not equal to the damage suffered by the injured party.

Therefore, if sufficiently detailed information is available, the income approach is frequently the first valuation choice.[29] The market approach and the cost approach, on the other hand, may provide a benchmark for the arbitral tribunal to directionally compare the damage derived under the income approach.

Endnotes

[1] Kai F Schumacher is managing director and Christoph Wilmsmeier is a director at AlixPartners in Germany.

[2] Irmgard Marboe, ‘Calculation of compensation and damages in international investment law’, 31–32 (2009); Mark Kantor, ‘Valuation for arbitration – compensation standards, valuation methods and expert evidence’, 16 (2008); see also Richard M Wise, ‘Quantification of economic damages’, 5 (1996).

[3] Something similar can apply to a difference in prices, which most often applies to merger and acquisition disputes and therefore is not a focus area of this chapter.

[4] Similarly, disputes between customers and telecommunications providers are not the focus of this chapter.

[5] International Valuation Standards 2022, IVS 105, Valuation Approaches and Methods, para. 10.1.

[6] Conceptually, the valuation process under the market approach contains three steps: (1) identify comparable assets (e.g., a peer group) and obtain the market prices of these assets; (2) put the obtained market prices in relation to a metric, such as EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation), EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) or SAC (subscriber acquisition costs) (i.e., convert the obtained market prices into a standardised multiple); and (3) apply this multiple to the underlying metric of the asset to be valued. Considering this valuation concept, damages can then be calculated as the difference in the underlying metric that has been caused by the wrongful act multiplied by the determined multiple.

[7] International Valuation Standards 2022, IVS 105, Valuation Approaches and Methods, Section 30.

[8] Sanjeev Bhojraj and Charles M C Lee, ‘Who is my peer? A Valuation-Based Approach of the Selection of Comparable Firms’, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 40 No. 2 (May 2002), p. 432.

[9] Aswath Damodaran, The Dark Side of Valuation: Valuing Young, Distressed and Complex Businesses (2nd Edition, 2010), p. 1.

[10] Bradford Cornell, ‘Discounted Cash Flow and Residual Earnings Valuation: A Comparison in the Context of Valuation Disputes’, Business Valuation Review, March 2013, p. 1; Efthimios Demirakos, et al., ‘What Valuation Models Do Analysts Use?’, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 18, No. 4; December 2014, p. 221. Several variations (or sub-methods) of the DCF method are used in practice. All these variations provide the same result if consistent assumptions are applied. Professor Fernández of the IESE Business School has shown in a study that there are 10 different sub-methods of discounting cash flows in valuation settings: Pablo Fernández: ‘Valuing companies by cash flow discounting: ten methods and nine theories’, Working Paper No. 451, abstract without numbering (2006).

[11] Moreover, it can be derived for any valuation date needed.

[12] For example, valuation standard set by the Institute of Public Auditors in Germany (the German CPA association), ‘Principles for the Performance of Business Valuations’ (IDW S 1), 19 (2008).

[13] Lucio Cassia, et al., ‘Equity Valuation Using DCF: A theoretical analysis of the long term hypothesis’, Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Vol. 4, Issue 1, 2007, p. 91.

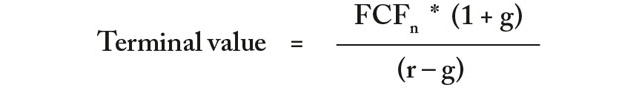

[14] id. Technically, the terminal value is derived from the following formula:

where: FCFn = free cash flow for the last forecast period; g = perpetual growth rate; and r = discount rate.

[15] Richard A Pollack, et al., ‘Calculating Lost Profits’, (2012), p. 51. Lost profit calculations are typically prepared on a pre-tax basis.

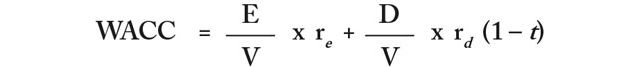

[16] Technically, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is derived from the following formula:

where: re = cost of equity; rd = cost of debt; t = tax rate; E = equity market value; D = debt market value; V = E + D = enterprise market value. For post-tax valuation, the deductibility of interest must be considered.

[17] International Valuation Standards 2022, para. 60.9.

[18] The concepts of liquidity and illiquidity refer to the degree of ease and certainty with which assets can be converted into cash.

[19] European Central Bank: Liquidity (Risk Concepts) – Definitions and Interactions, p. 18 (2009).

[20] ibid., pp. 14–15.

[21] Aswath Damodaran, ‘Marketability and Value: Measuring the Illiquidity Discount’ (2005), p. 34.

[22] The illiquidity discount is often applied to both controlling and non-controlling interest. However, individual characteristics of the legislation and related guiding valuation principles are to be considered as well: for example, illiquidity and marketability discounts are not considered in German court cases.

[23] Damodaran, op. cit. note 21, p. 28 et seq.

[24] Aswath Damodaran, ‘The Value of Control: Implications for Control Premia, Minority Discounts and Voting Share Differentials’ (2005), p. 2.

[25] By considering the acquisition premium as the difference between the price actually paid for acquiring the controlling stake and the previous market price before the transaction was announced, this may be overstating or understating the effects solely attributable to control due to other effects also comprising the acquisition premiums, such as synergies, competitive pricing or other transaction-specific characteristics.

[26] International Valuation Standards 2022, IVS 105, Valuation Approaches and Methods, para. 60.1.

[27] Queen Mary University of London and PwC, ‘Damages awards in international commercial arbitration, A study of ICC awards’, (2020, p. 14. The study examined 180 awards in arbitral proceedings administered by the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris and New York between 2014 and 2018.

[28] It is also possible to include mitigating factors in the market approach. However, this is usually much more complex, as the effects of mitigation would need to be transformed into an annuity, which is then considered in the multiple-based valuation.

[29] Unless there are other circumstance to the contrary. An example for such circumstances would be a post-M&A dispute where an excess purchase price paid is claimed and the purchase price paid was derived by another method, then the same method should usually be applied when determining the overpayment.