When prices go wild: the impact of high inflation on valuation, damages and disputes

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of GAR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

Inflation has increased in recent years above the historical norms of the previous two decades across most economies. This situation brings additional challenges to the valuation of assets and assessment of damages. This article, which focuses on Latin America, highlights how inflation affects: (1) valuations, regardless of the valuation method used; and (2) the assessment of damages, also bringing more economic relevance to issues such as the date of assessment and pre-award interest rate. Lastly, the article also provides examples of high inflation being itself the cause of new disputes.

Discussion points

- The global underlying causes of the recent resurgence of high inflation

- The impacts of high inflation on each of three of the most commonly used asset valuation methods

- The impacts of high inflation on the assessment of damages

- How high inflation may have a substantial bearing on damages depending on the date of assessment

- How high inflation may be considered in any pre-award interest in an assessment of damages

- Instances where inflation itself is the cause of disputes

Referenced in this article

- ConocoPhillips Petrozuata BV, ConocoPhillips Hamaca BV, ConocoPhillips Gulf of Paria BV and ConocoPhillips Company v Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

- National Grid PLC v Argentine Republic

Introduction

The post pandemic world has seen a resurgence of high inflation in developed and developing economies alike, and Latin America has been no exception. In this article, we first examine the recent resurgence of high inflation and the reasons behind it, with a special focus on Latin America. We then explain how (high) inflation impacts the valuation of assets and how it also affects the assessment of damages, including relevant considerations when determining the date of assessment and pre-award interest. We finally conclude with examples of disputes in Latin America where inflation has played a major role.

Inflation is back at the forefront of issues

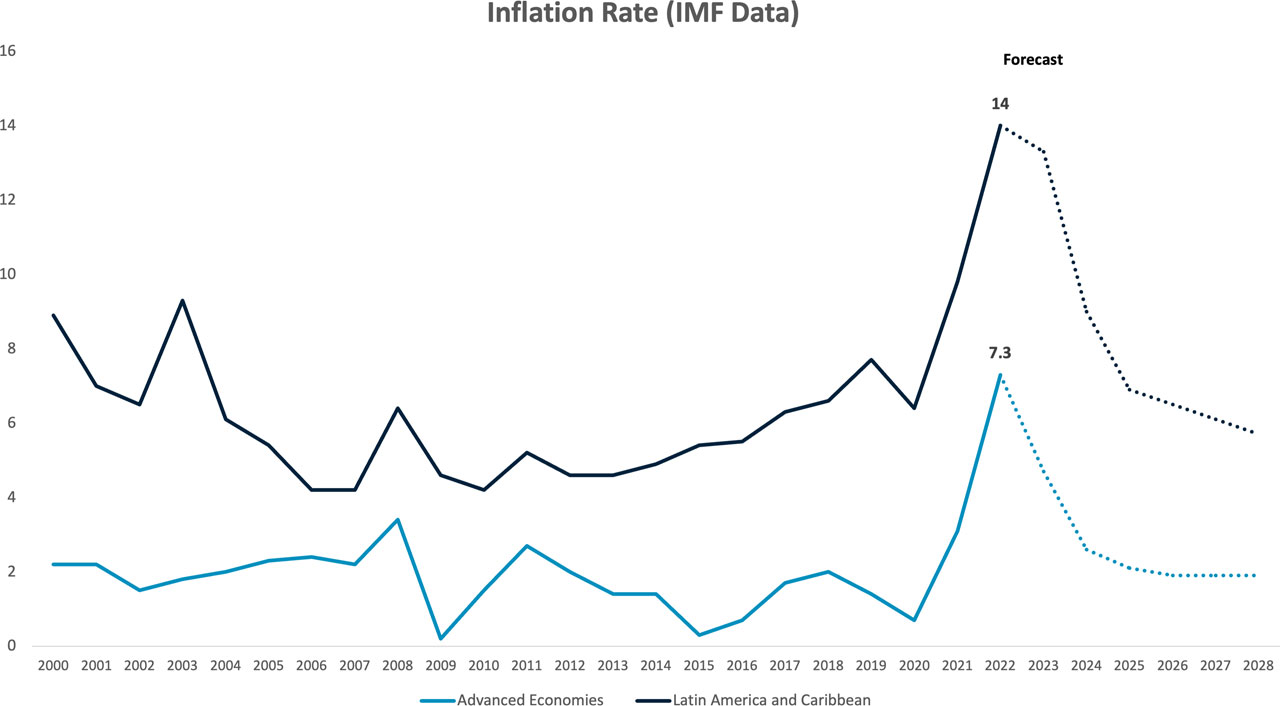

After more than 20 years of relatively stable prices and tame inflation rates (2000–2020), the world has recently experienced a reappearance of high inflation, with a peak average inflation rate in 2022 of 7.3 per cent among developed economies, and 14 per cent across Latin America and the Caribbean.

Figure 1. Inflation Rate, percentage per year, historical and forecast (IMF)

The underlying causes of this return of high inflation have been similar in both Latin America and in developed economies.

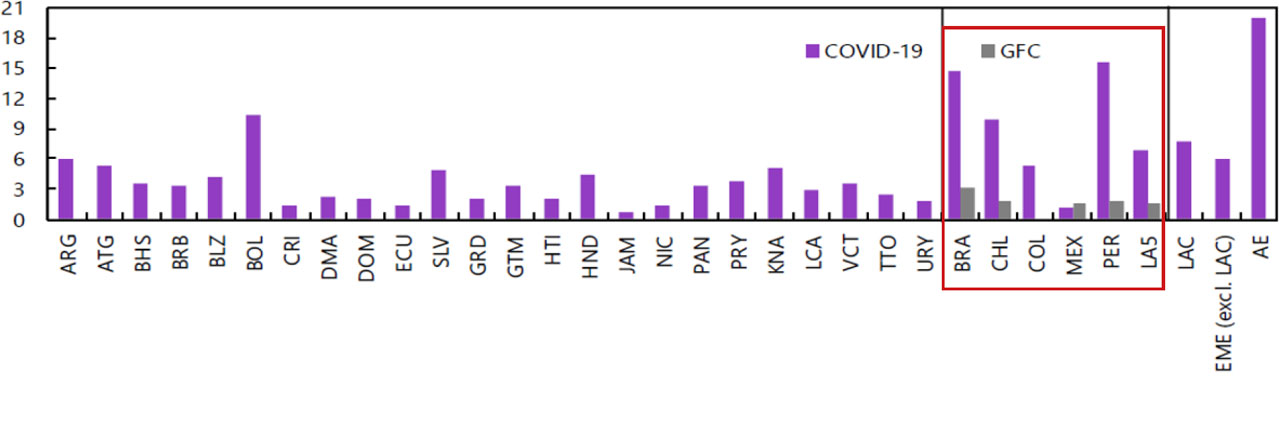

Firstly, governments reacted to the covid-19 pandemic with unprecedented fiscal stimulus. For instance, a 2020 paper published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows that discretionary measures implemented by the governments of Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru during the pandemic were significantly higher than fiscal packages conducted by these countries during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 2. Discretionary fiscal measures in the Global Financial Crisis (implemented) and covid-19 (announced), as a percentage of GDP

Source: ‘Fiscal Policy at the Time of a Pandemic? How have Latin America and the Caribbean Fared’, October 2020

Secondly, restrictive measures imposed by many countries as a means to tackle the pandemic – and the emergence of the Russia–Ukraine conflict – caused significant disruption to global supply chains, leading to shortages of many goods and key components, from food to energy and semiconductors. The table below shows the increase in selected commodity price indices in 2022 versus 2019.

Table 1. IMF Commodities’ Indices (2022 average v 2019 average)[1]

| Index | 2019 average | 2022 average | Percentage increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food | 99.37 | 147.40 | 48.3 |

| Metals | 124.08 | 169.88 | 36.9 |

| Energy | 129.28 | 299.51 | 131.7 |

Amid supply shortages, increased government spending, with policies such as direct cash transfer to citizens, has led to higher demand for goods and services. This combination of reduced supply and increased demand culminated in a significant increase in inflation.

Currency devaluation was another key factor that further contributed to the recent upsurge in Latin American inflation, as a weaker currency translates into higher prices in local terms for imported products or for products priced in US dollars, which is generally the case for commodities. The table below shows the evolution of the exchange rate in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

Table 2. Exchange rates of selected Latin American countries, local currency per US dollar[2]

| Currency | 2019 average | 2022 average | Percentage devaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian real | 3.94 | 5.16 | 30.9 |

| Chilean peso | 702.90 | 873.31 | 24.2 |

| Colombian peso | 3,281.62 | 4,256.19 | 29.7 |

| Mexican peso | 19.26 | 20.13 | 4.5 |

| Peruvian sol | 3.34 | 3.84 | 14.9 |

Against this backdrop, high inflation has become a significant concern for policymakers in the region. High inflation not only poses a threat to economic stability, but also reduces the purchasing power of citizens, leading to a challenging environment for individuals and businesses. According to poll data from FTI Consulting’s 2022 Resilience Barometer,[3] of the top five main boardroom concerns across 26 surveyed territories, including all G-20 countries, two are related to inflation: a surge in energy prices (cited by 36 per cent of respondents); and inflation reaching damaging levels (32 per cent of respondents). In Latin America, the same poll shows that 55 per cent of respondents in Brazil and Argentina cite inflation reaching damaging levels as a reason for concern. In Chile this figure was 38 per cent, and in Colombia 37 per cent; all above the 32 per cent average level for G-20 countries.[4]

These figures clearly indicate how inflation has become a major issue for policymakers and businesses alike, particularly in Latin America. Inflation has also been at the forefront of issues for Latin American voters. According to a poll from Brazilian research institute Datafolha conducted during the 2022 election, inflation and fuel prices were among the chief concerns when voting for a new government.[5] In Argentina, according to an article published by iProfesional, inflation was the most cited concern of Argentinian voters as the 2023 presidential election approaches, chosen by 92 per cent of respondents in a multiple-choice poll; albeit, Argentina’s high inflation extends far beyond the recent period and circumstances described above.[6]

Although the increase in inflation seen over the past few years is widely expected to be temporary, IMF forecasts only envisage inflation rates returning to pre-pandemic levels by 2025 (see Figure 1). Hence, the challenges posed by inflation are far from over, including in respect of conducting business valuations, as explained below.

Impacts of (high) inflation on valuation

In general terms, the value of an asset is a function of the future cash flows that the asset is expected to generate, and the risk associated with these expected future cash flows. Assets that are expected to generate higher cash flows with a lower risk are inherently worth more than assets that are expected to generate lower cash flows with a higher risk.

Future cash flows are a function of future inflation, among other things. Therefore, any valuation methodology needs to consider inflation in one way or another. When inflation is low and stable, and there are no factors that indicate a change to this trend in the foreseeable future, inflation is unlikely to be a cause of concern or disagreement between valuers. However, as we explain below, when inflation is high and unstable, it can potentially lead to significant disagreement between valuers.

Valuation methods

There are three main approaches commonly used when valuing an asset: income-based, market-based and cost-based. We present below a brief summary of each approach.

Income-based valuation methods are based on the future economic benefits expected to be generated by the asset being valued. The most common income-based valuation method is the discounted cash flow (DCF), which values an asset based on the present value of its expected future cash flows. Under a DCF approach, the valuer follows a two-step process, first estimating the future cash flows the asset is expected to generate, and then combining these cash flows into a single figure that represents the present value of all future cash flows. To arrive at the present value, the valuer discounts future cash flows using a discount rate that accounts for both the ‘time value of money’ – given that US$1 now is worth more than US$1 tomorrow – and the risk associated with the future cash flows – given that future cash flows are uncertain.

Market-based valuation methods value the subject asset by considering what the market is willing to pay for similar assets, for example, in publicly traded equity or in an M&A transaction. The idea behind the market-based approach is that similar assets should be worth similar amounts, with adjustments made to reflect – among other factors – the size (eg, revenues) and profitability (eg, EBITDA,[7] or an alternative measure of earnings) of the traded assets in comparison to the target asset. Transactions of comparable assets provide a guide as to what the target asset is worth, assuming that the traded asset or the market as a whole has not significantly changed between the transaction date and the valuation date.

Cost-based valuation methods derive the value of an asset by adding up its purchase cost (or cost to replicate) less any accumulated depreciation. This method is generally not preferred as it does not take into account the value that could be generated by the underlying asset. In the valuation of a company, for example, it does not account for intangible assets that are not recorded on the company’s balance sheet, such as patents, processes, copyrights or customer relationships.

High inflation impacts all valuation methods, albeit in different ways

The DCF is a forward-looking valuation method, so only future inflation expectations are relevant to a DCF analysis. Past inflation will only be relevant to the extent that it informs expectations of future inflation. In a DCF analysis, expected inflation affects: the future cash flows that the target asset is expected to generate; and the rate used to discount future cash flows.

When projecting a company’s future cash flows, a valuer will need to consider its revenues and costs. High inflation will typically result in both revenues and costs increasing over time, but these are unlikely to move in line with inflation. Inflation is, by definition, a measure of the average increase in prices in a given economy, and the prices of certain goods will rise more or less than the rate of inflation. Hence, when forecasting a company’s future cash flows in the context of high inflation, a valuer should give special consideration to issues such as:

- long-term pricing contracts with customers or suppliers, which may keep prices fixed or update them according to some index;

- ‘cost-plus’ pricing, whereby the end prices charged by a company reflect a constant profit margin over input costs, which themselves may have risen more or less than the general rate of inflation, depending on the mix of inputs used; and

- how price increases may affect demand for a product, a concept known in economics as the ‘price-elasticity of demand’. High inflation may lower consumer’s purchasing power, reducing demand for a company’s goods. Additionally, if the prices of a company’s goods are increasing more than the prices of goods that are considered substitutes by consumers, then this may further lower demand for these goods.

In addition, high inflation may affect the discount rate a valuer applies to a company’s future cash flows in a DCF analysis in two ways:

- by increasing the ‘time value of money’: if the price of goods is expected to keep increasing over time, consumers may prefer to spend their money sooner rather than later; and

- by increasing the risk of the asset being valued: periods of high inflation are generally associated with higher economic uncertainty, including a greater risk of bankruptcy, meaning that investors may require a higher premium to invest in riskier assets.

As described above, market-based valuation methods are based on comparable assets. In a high-inflation environment, identifying suitable comparable companies may become more challenging if the markets in which comparable companies sell their goods experience significantly different inflation rates to those of the target company.

Analysing past transactions in comparable companies may also be problematic in high-inflation environments, as the price paid in past transactions should have incorporated inflation expectations as of the transaction date, and it may be challenging to adjust this price to account for any unexpected inflation since the transaction date.

Cost-based valuation methods normally rely on the historical value of assets. In a high-inflation environment, the costs paid for assets in the past will not resemble current costs to replace the same assets, reducing their suitability as a valuation method.

Impact of (high) inflation on disputes

High inflation may also affect disputes and damages assessments, in at least three ways:

- in the assessment of damages, as high inflation both increases the scope for disagreement between valuers, as discussed above, and makes legal considerations such as the date of assessment more economically relevant;

- in the pre-award interest to be applied to the calculated damages, which may be lower than the rate of inflation (whether this is relevant depends, however, on the purpose of interest); and

- in being itself the cause for disputes, as increased prices may cause projects or companies to become economically unviable.

The impact of high inflation in the assessment of economic damages

Economic damages are often calculated as the difference between the cash flows in the actual scenario – in which the damaging event occurred – and the counterfactual scenario – in which the damaging event did not occur. In these cases, quantum assessments in the context of disputes will need to grapple with the valuation issues discussed above.

The award rendered in the ConocoPhillips v Venezuela arbitration provides an example of when the tribunal had to deal with issues related to inflation in the assessment of damages.[8] On the revenue side, the tribunal considered that the assumption made by the claimant’s expert that oil prices must be connected to US inflation was ‘overly simplistic’[9] as they observed ‘a number of recent years when oil prices were moving whereas inflation remained stable in many countries’.[10] The respondent, on the other hand, alleged that ‘no certainty [was] available as from year 2020 and that therefore a flat rate should be used until the end of each Projects’ lifetime’.[11] On the cost side, the tribunal acknowledged the difficulty of considering inflation, given that there were costs in two currencies: ‘The difficulty in the present matter results from the fact that a number of items on costs imply US$ and Bolivars, when these two currencies are applicable to specific parts of a same cost item. Therefore, to the extent that this is relevant, inflation must be determined separately for each currency.’[12]

The higher the rate of inflation, the more likely that issues around the forecasting of cash flows and the estimation of discount rates will be a source of disagreement among experts, and the more likely that tribunals will need to engage with these issues.

In addition, high inflation will bring more economic relevance to legal issues that tribunals need to consider, such as the appropriate date of assessment. Typically, damages are assessed on one of two dates:

- the date of the illegal act, misconduct or omission, often referred to as ‘date of breach’; or

- the date of the award, for which the ‘date of hearing’ is often used as a proxy.

The choice of assessment date affects the mechanics of the calculation but, most importantly, it affects the information that may be used to assess losses. In a damages assessment as at the date of breach, hindsight is usually avoided. Therefore, any event that occurred after the breach, which was not expected at the time of the breach, will normally not be considered in the calculation. On the other hand, in a damages assessment as at the date of hearing, any unexpected event that occurred since the date of breach can be factored into the damages calculation, as a date of hearing assessment will consider what actually occurred after the date of breach.

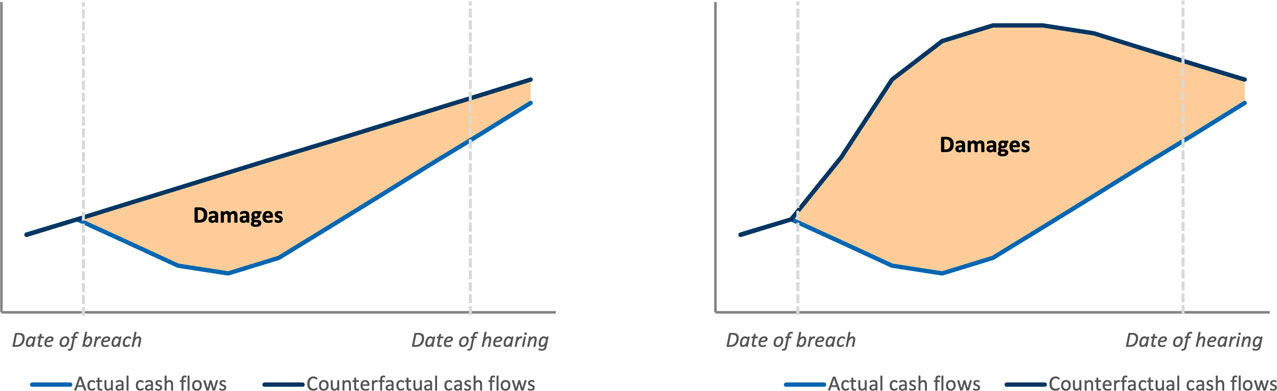

Hence, in a high-inflation environment, different dates of assessment may lead to significantly different calculated damages. For example, imagine a case of lost profits in an industry whose products significantly increased in price between the date of breach and the date of hearing – as has recently been the case for several commodities, as illustrated earlier in this article. If damages are assessed as at the date of breach, the actual increase in sale prices would usually not be considered in the calculation, as only information as of the date of breach would be considered – ie, the expected price increase. On the other hand, if damages are assessed as at the date of hearing, the actual price increase will be considered, which would lead to an increase in assessed damages. This is shown in the illustrative figure below.

Figure 3. Graphical representation of differences between a date of breach and date of hearing damages assessment

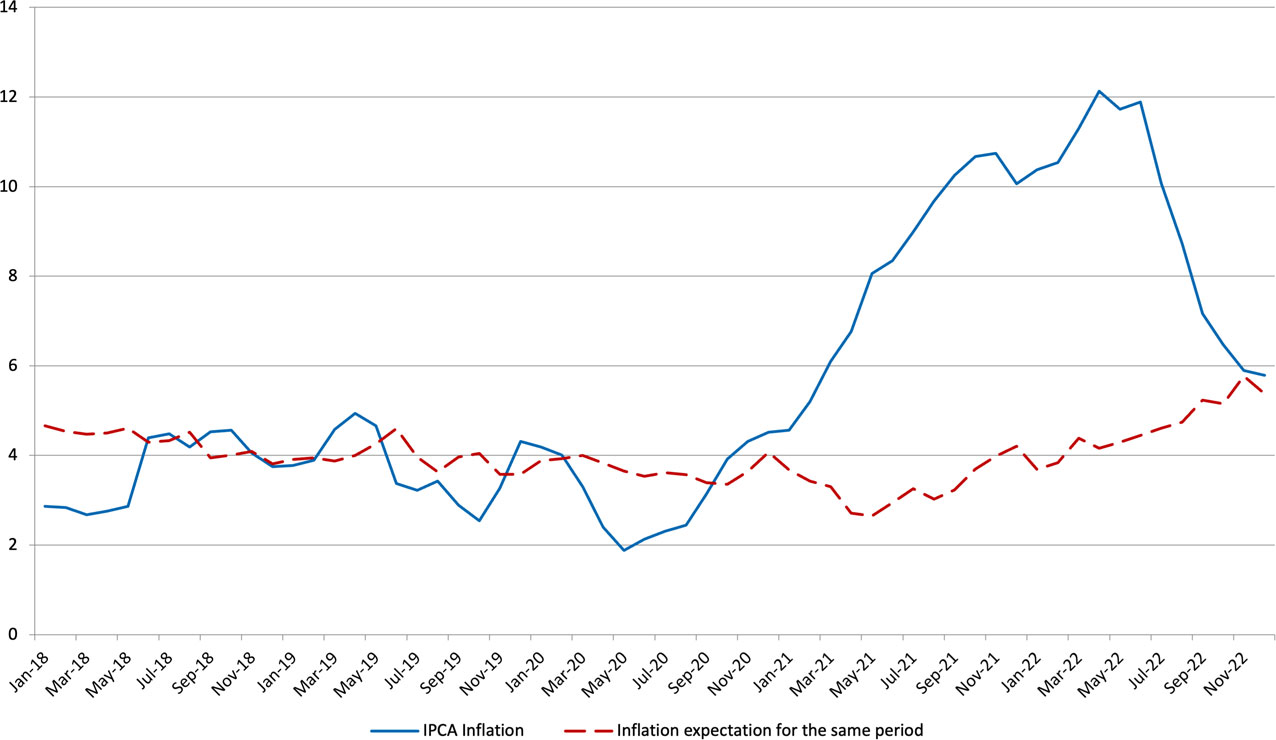

This illustrative example highlights the impact on damages assessments that may materialise when actual inflation turns out to be much higher than expected inflation. This was the case for Brazil from 2020 to 2022, when consumer price inflation (as measured by the IPCA)[13] turned out to be much higher than expected inflation, as shown in the figure below. In such an environment, the choice of the date of assessment becomes even more relevant.

Figure 4. IPCA inflation (last 12 months, per cent) and IPCA expected inflation (for the next 12 months, with a lag of 12 months, per cent)

Note: Brazilian Central Bank. Actual inflation is the accumulated IPCA (see footnote 13 for more details on this measure of inflation) over the past 12 months, from https://www3.bcb.gov.br/sgspub (accessed on 15 May 2021 by selecting index code 13522, from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022). Inflation expectations from https://www3.bcb.gov.br/expectativas2/#/ consultaSeriesEstatisticas (accessed on 15 May 2021 by selecting ‘Índices de Preços’, ‘Horizontes Móveis’, ‘IPCA’, ‘Expectativas informadas nos últimos 5 dias úteis’, ‘Mediana’, from 1 January 2017 to 31 March 2023).

The impact of high inflation on pre-award interest

High inflation may also bring up some additional considerations when determining pre-award interest. Awards assessed by a tribunal are typically updated to compensate for any loss of value over time, so the question then becomes which interest rate should be used to update this amount. Tribunals have a large number of options, sometimes restricted or informed by the applicable law, for example: a flat rate of interest, a variable rate of interest (such as LIBOR plus a spread)[14] and inflation indices.

In National Grid v Argentina, when deciding on the pre-award interest rate to be applied to the award, the tribunal used the claimant’s cost of debt on the basis that it would be realistic to assume the:[15]

‘Claimant would have applied the sums received either to eliminate existing debt or avoid incurring additional debt. We believe, therefore, that the appropriate interest rate to be applied from June 25, 2002 forward to the date of the Award should be an average interest rate which Claimant would have paid to borrow from that date to the present.’

In addition, when discussing the post-award interest, the tribunal considered that ‘the function of post-award interest is essentially to protect the value of the Award against inflation’,[16] but they also recognised that ‘the subject of post-award interest remains a matter in which arbitral tribunals have adopted a variety of approaches’.[17]

If a pure inflation rate is used to update an award, it could be said that the claimant would not be fully compensated for its losses, as it could be argued that any monetary award received in the past could have been invested at a base interest rate[18] (or higher), increasing its value. However, using a base interest rate in periods of high inflation may also not fully compensate claimants for changes in purchasing power, to the extent that this is a relevant consideration, as these rates may be lower than inflation.

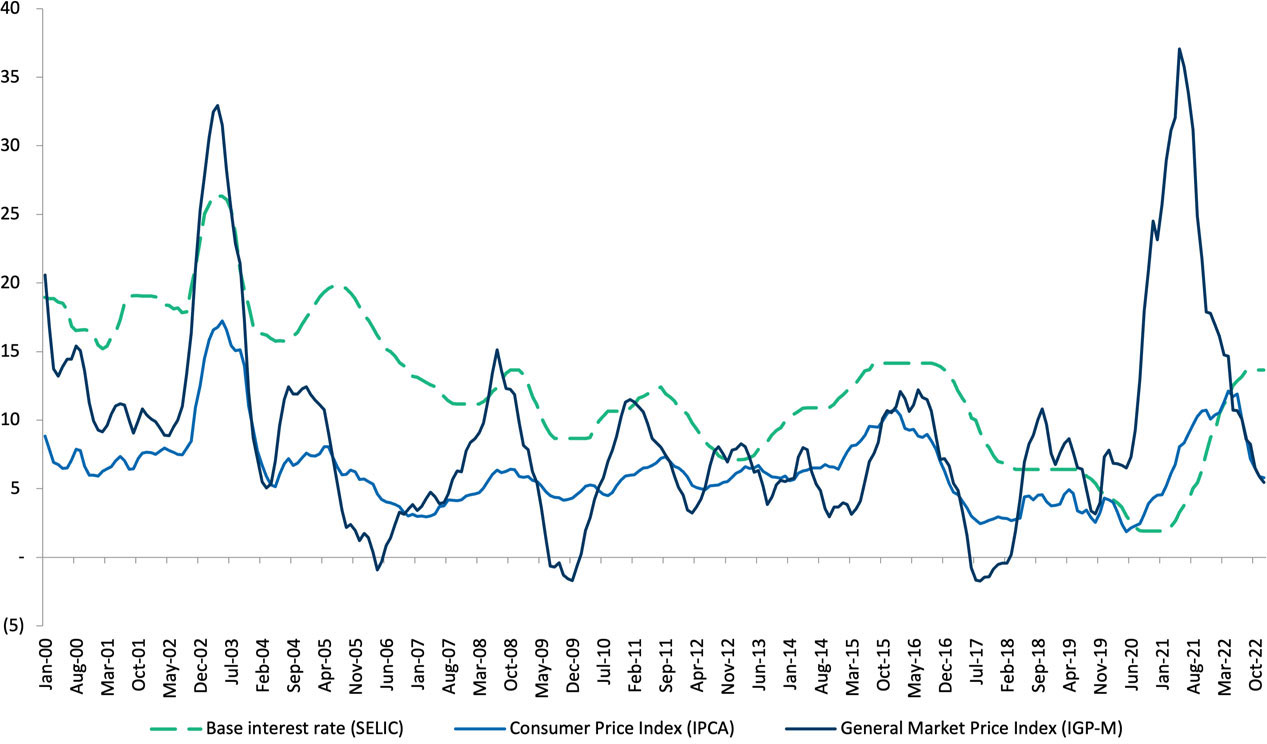

In the case of Brazil, there has historically been much debate on the applicable rate to be used to update damages,[19] given the high volatility of inflation and interest rates in the country. Brazilian courts of justice will typically apply a monetary update to awards based on historical inflation, plus a default interest rate of 1 per cent per month – ie, an update that will always compensate for historical inflation. However, more recently, the Brazilian Superior Court of Justice has rendered decisions that apply the base interest rate instead. In their understanding, the base interest rate should compensate for both inflation and interest, although this may not be always the case.[20] For example, the recent evolution of interest rates and inflation in Brazil demonstrates a scenario in which inflation has outpaced the base interest rate, and also where different inflation indices have greatly differed. In December 2020, we had the following situation:

Figure 5. Brazilian base interest rates and inflation indices (per cent)

Note: Brazilian Central Bank: https://www3.bcb.gov.br/sgspub (accessed on 15 May 2021 by selecting index codes 13522 and 189, from 1 December 1998 to 31 December 2022, and index code 4189 from 1 December 2000 to 31 December 2022).

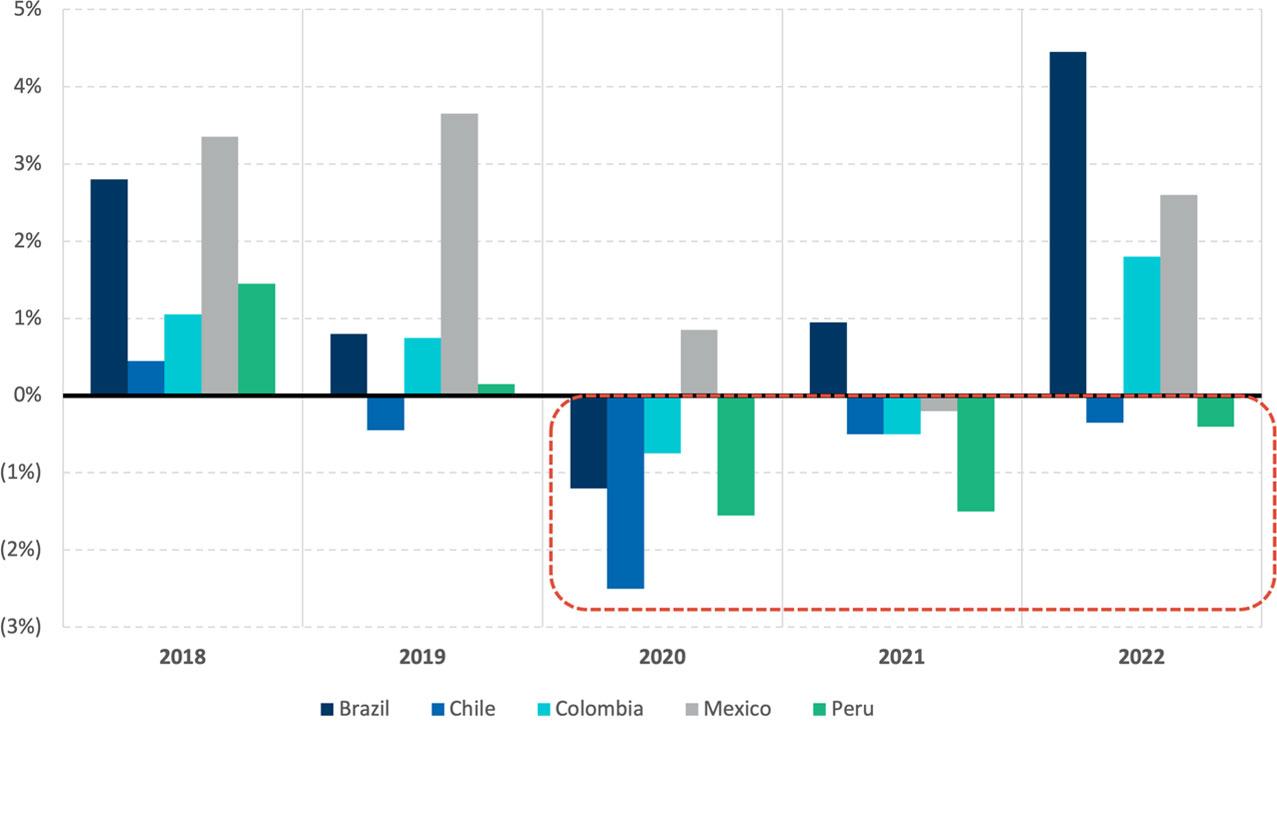

A similar situation has arisen in other Latin American countries since the onset of the pandemic, as can be seen in Figure 6, which shows the result of subtracting the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate (a commonly used rate of inflation, analogous to the IPCA inflation rate in Brazil) from the base interest rate[25] in five large Latin American economies. When this figure is below zero, it means that inflation has outpaced the base interest rate in that country in that year.

Figure 6. Base interest rates less CPI inflation for selected Latin American economies

Source: IMF Data (https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PCPIPCH@WEO/ADVEC/WEOWORLD).

Therefore, since the pandemic, awards updated by base interest rates would not compensate claimants for inflation in many Latin American economies. However, whether the purpose of an award of interest is to compensate claimants for losses in purchasing power, among other factors, is a matter of law.

When inflation itself is the cause of disputes between parties

In some cases, inflation itself can be the origin of disputes, for example in specific cases where one of the authors of this report has acted as an expert. These disputes originated from large and unexpected price increases, one related to a real estate lease and the other related to a solar energy project.

The first case is a confidential dispute between Brazilian companies that were parties in a real estate lease contract. Leases in Brazil have historically been adjusted by an inflation index known as IGP-M. The IGP-M index is composed of a basket of three indices: a consumer price index, a wholesale price index; and a construction price index. The wholesale price index includes commodities in its calculation, such as minerals, oil and cellulose. In addition, this index has the highest weight (60 per cent) in the IGP-M basket. As commodities are usually priced in US dollars, the exchange rate also plays an important role in the evolution of the IGP-M.

Between 2019 and 2022, commodity prices increased steadily and the Brazilian currency devalued by 30.9 per cent, as shown in the first section of this article. This led to the IGP-M increasing by 23.1 per cent in 2020, while the IPCA[26] increased by only 4.5 per cent in the same year. As a consequence, rental contracts were impacted by an unusually high inflation rate. The differential between both inflation indices, at 18.6 percentage points, was also unprecedented historically.

Given this, the claimant sought to change the inflation index in the contract, as its revenues had grown at a rate below the IPCA (4.5 per cent), while its rental cost increased by the IGP-M (23.1 per cent). This led to the firm’s rental costs accounting for a significant portion of its revenues, severely compromising the economic viability of the business. Unsuccessful negotiations with the lessor led the lessee to initiate an arbitration to discuss the replacement of the inflation index in the contract from IGP-M to IPCA. A multitude of similar cases have appeared in Brazilian courts since the onset of the pandemic.[27]

The second case relates to a dispute in a solar energy project, where the claimant had entered into energy purchase price agreements (PPAs) with the respondent, just prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. The construction of the solar plant was originally planned for the second half of 2020, precisely when the prices of the main components required to build the plant increased significantly. These prices would remain elevated for another year. The increase in prices significantly impacted the capital expenditures required for the construction of the plant, leading the claimant to initiate an arbitration to renegotiate the PPA, as the project had become economically unviable.

Conclusion

Regardless of the valuation method used, inflation affects valuations. Especially in periods of high inflation, as seen from 2020 onwards, inflation may foster disagreement between valuers, as the higher the inflation rate, the greater the potential impact on the valuation assessment.

As the assessment of damages is also often based on a projection of cash flows and the estimation of a discount rate, the issues that affect valuation as a result of high inflation will often also impact damage assessments. Moreover, high inflation may bring more economic relevance to some of the issues tribunals generally need to grapple with, such as the date of assessment and the pre-award interest rate.

Lastly, in a high inflation environment, inflation itself can be the origin of disputes, as large and unexpected price increases can lead to significant impacts to businesses, and the need to renegotiate contracts.

Given the above, and considering how current inflation expectations show that inflation is not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2025, we expect to see both more inflation-related disputes and disputes where inflation brings additional challenges to the assessment of damages in the coming years.

* The authors would like to thank Bruno Carbonari (senior director, FTI Consulting), Guilherme Schreuders (senior director, FTI Consulting), Sergio Berruezo (manager, FTI Consulting) and Connor Gower (senior consultant, FTI Consulting) for their contributions to this article.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Research/CommodityPrices/Monthly/external-datamay.ashx. The indices used were: (1) Food Price Index (column F); (2ii) All Metals Index (column K); and (3) Fuel (Energy) Index (column P).

[2] International Financial Statistics (IFS) data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

[3] FTI Resilience Barometer, January 2022.

[4] FTI Resilience Barometer, January 2022.

[5] ‘Datafolha: Em ano eleitoral, saúde e economia lideram preocupações do brasileiro’, 25 March 2022 (https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2022/03/datafolha-em-ano-eleitoral-saude-e-economia-lideram-preocupacoes-do-brasileiro.shtml#).

[6] ‘Se hunde la imagen del Gobierno y crece el pesimismo: cuáles son los 10 temas que más preocupan a los argentinos’, 06 April 2023 (https://www.iprofesional.com/politica/379934-encuesta-conoce-los-10-temas-que-mas-preocupan-a-los-argentinos).

[7] Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.

[8] ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10402.pdf.

[9] ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, paragraph 702, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10402.pdf.

[10] ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, paragraph 702, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10402.pdf.

[11] ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, paragraph 703, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10402.pdf.

[12] ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30, paragraph 625, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10402.pdf.

[13] Specifically the IPCA or Extended National Consumer Price Index.

[14] LIBOR is largely no longer in use as of 2022 (https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/announcements-end-libor).

[15] UNCITRAL Case 1:09-cv-00248-RBW, paragraph 294, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0555.pdf.

[16] UNCITRAL Case 1:09-cv-00248-RBW, footnote 122, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0555.pdf.

[17] UNCITRAL Case 1:09-cv-00248-RBW, footnote 122, at https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0555.pdf.

[18] Refers to the interest rate defined by central banks in the context of their monetary policy. In Brazil, the base interest rate is the SELIC (https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/monetarypolicy/selicrate).

[19] See, for example: https://www.conjur.com.br/2021-jan-06/edilton-meireles-uso-taxa-selic-correcao-monetaria; and https://www.stj.jus.br/sites/portalp/Paginas/Comunicacao/Noticias/2023/01032023-Relator-vota-contra-utilizacao-da-taxa-Selic-para-a-correcao-de-dividas-civis.aspx.

[20] See, for example: https://www.conjur.com.br/2021-jan-06/edilton-meireles-uso-taxa-selic-correcao-monetaria; and https://www.stj.jus.br/sites/portalp/Paginas/Comunicacao/Noticias/2023/01032023-Relator-vota-contra-utilizacao-da-taxa-Selic-para-a-correcao-de-dividas-civis.aspx.

[22] https://valorinveste.globo.com/mercados/brasil-e-politica/noticia/2021/01/12/ipca-surpreende-em-dezembro-e-fecha-2020-em-452percent-maior-alta-desde-2016.ghtml.

[23] Specifically, the IGP-M or General Market Price Index.

[24] https://portalibre.fgv.br/noticias/igp-m-sobe-087-em-dezembro#:~:text=Em%20dezembro%20de%202020%2C%20o,partiu%20do%20%C3%ADndice%20ao%20produtor.

[25] Defined as the ‘Monetary policy related interest rate’ in International Financial Statistics (IFS) data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=63087881).

[26] The IPCA (see endnote 14) is a consumer price index calculated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, and is mainly comprised of food and beverages, housing, health and education costs. As such, the IPCA aims to reflect the consumption profile of typical Brazilian families, and is much less impacted by fluctuations in the exchange rate than the IGP-M (see endnote 25).