Italy

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of GAR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

Recent developments have occurred in the past years, which should allow Italy to increase its role in the context of international arbitration. The newly adopted rules of the Italian Code of Civil Procedure addressed in this article demonstrate the legislator’s intention to render arbitration proceedings more effective. The same goes with the introduction of the emergency arbitrator and simplified arbitration procedure adopted by the Chamber of Arbitration of Milan, which gives the parties the opportunity to choose faster and cheaper arbitration, while maintaining a high level of arbitrators’ expertise. Finally, this article will touch upon recent decisions of the Italian Supreme Court, which go in the direction of ensuring certainty and predictability in arbitration procedures. In conclusion, Italy is and remains a valid option for where to seat arbitration proceedings.

Discussion points

- Arbitrator’s independence, impartiality and appointments

- Interim measures

- Corporate arbitration

- Challenge to awards and enforcement

- Case law highlights

Referenced in this article

- Legislative Decree No. 150 of 10 October 2022, implementing Law No. 134/2021 (Cartabia Law or Reform)

- Italian Code of Civil Procedure (ICCP)

- Legislative Decree No. 5/2003 (Corporate arbitration decree)

- Arbitration Rules of the Milan Chamber of Arbitration

- Recent Italian case law in the field on arbitration

Foreword

An overview of the current Italian arbitration legislation and practice cannot be done without a brief examination of the context relating to the Italian civil justice system.

The chronic problem that has gripped the administration of justice in Italy (ie, the heavy backlog of undisposed proceedings) appears to have veered towards improvement: according to an authoritative report by the Bank of Italy,[1] in 2019 the number of pending civil cases shrunk by 37 per cent compared to 2010, with a consequent considerable reduction in the disposition time (ie, the average foreseeable time for the disposal of processes, which remains of approximately 470 days).

In said period, the Italian legislator has promulgated several measures aimed at developing alternative dispute resolution tools, the last of which – and the most significant for its impact on the discipline of arbitration – is represented by Legislative Decree 150 of 2022 (Cartabia Law or Reform).

On the subject of arbitration, the Reform has tackled some of the aspects, which, according to Italian practitioners, fell among the most deserving profiles of revision: the Italian Code of Civil Procedure (ICCP), which contains the main national provisions on arbitration law, has indeed seen new rules on (1) the independence and impartiality of arbitrators, (2) the granting of interim measures by arbitrators (previously absent), (3) the relationship between ordinary civil proceedings and arbitration proceedings (with new rules on resumption) and (4) the review of the rules on corporate arbitration – an aspect that is rather heartfelt, given the frequent use of the arbitration clause that Italian practice makes in the articles of association of partnerships and corporations.

The legislative context of arbitration in Italy therefore appears to be increasingly favourable for arbitration practice and oriented to the needs of the community; however, the problem of a civil justice system that is not always up to the needs remains in the background and may also have negative consequences for the proper functioning of arbitral justice, in particular with regard to the risk of delays and bottlenecks in judicial proceedings that may arise in parallel with or following an arbitration award.

In this regard, the innovations introduced by the Reform may serve to increasingly free arbitration from the critical issues arising from a judicial system that fights with its own inefficiencies and to align it with international standards.

In any case, the best guarantee of efficiency, speed and cost-effectiveness of the arbitration procedure is provided by recourse to arbitration administered by reputable institutions that have adopted regulations and practices in line with those applied internationally. To date, the main institution for the administration of arbitration proceedings in Italy is the Chamber of Arbitration of Milan (CAM), which currently administers over a hundred proceedings simultaneously, 23 per cent of which have international nature;[2] in particular, as of 1 July 2020, CAM has adopted the Simplified Arbitration Procedure, applicable to all claims not exceeding €250,000 unless one of the parties opts-out and, under an opt-in regime, to all arbitrations regardless of the value of the claims. Said procedure offers a reduction both in terms of costs and time.

We will deal below in separate chapters on the main significant aspects affected by the Reform.

Independence, impartiality and appointments

Independence and impartiality

The arbitral tribunal may be composed of a sole arbitrator or of an arbitration panel made up by an odd number of arbitrators to ensure its functioning. The number of arbitrators and their method of appointment (by the parties or by an institution) shall be specified in the arbitration clause.

Every arbitrator must remain impartial and independent throughout the proceedings. To strengthen these guarantees, the Reform has made it mandatory, under penalty of nullity, for each arbitrator to declare in the statement of acceptance any circumstances that could limit their independence and impartiality, or the non-existence of the same.

The arbitrator shall disclose any facts and circumstances that might be of such a nature as to call into question the arbitrator’s independence in the eyes of the parties even if not such as to prevent their acceptance. The statement of independence shall be repeated in the course of the proceedings, if necessary due to supervening facts.

If the arbitrator fails to submit the aforementioned declaration, each party may request the judicial authority to remove the arbitrator, within 10 days from the acceptance made without the declaration or from the discovery of the relevant undisclosed circumstance, after sending a notice to the arbitrator to provide the missing disclosure.

Finally, if the declaration is not requested and the arbitrator does not provide any disclosure at the time of the acceptance, the invalid constitution of the arbitral tribunal integrates one of the grounds to challenge the validity of the award, provided that the nullity has been raised in the arbitral proceedings.

With a view to strengthening independence and impartiality, the Reform has introduced a new ground for challenging the appointment of the arbitrator (ie, a general reference to other and material reasons of convenience affecting the arbitrator's independence or impartiality). In practical terms, the challenge must be submitted to the President of the Tribunal, within ten days from the notification of the appointment or from the knowledge of the ground for challenge.

Independence pursuant to CAM Rules

Under CAM Rules, the statement of independence must indicate the following: (1) any relationship with the parties, their counsels and any other person or entity involved in the arbitration, even on a financial relationship basis (for example, in case of dispute financed by a third party), which may affect their impartiality or independence, (2) any personal or economic interest, either direct or indirect, in the dispute and (3) any bias or reservation as to the subject matter of the dispute. Within 10 days of receipt of the disclosure, the parties may submit their comments, if any, and, thereafter, the CAM Arbitral Council shall decide on confirmation or non-confirmation.

Appointment criterias

As the appointment of arbitrators constitutes an essential moment for the success of the proceedings, in addition to competence in the matter and the requirements requested by the arbitration clause, the parties and, above all, the institutions consider the following additional elements:

- geographical neutrality, particularly when the parties are of different nationalities (see article 15 CAM Rules, according to which ‘Where the parties have different nationalities or registered offices in different countries, the Arbitral Council shall appoint as sole arbitrator or president of the Arbitral Tribunal a person of a nationality other than those of the parties, unless otherwise agreed by the parties’);

- gender. It is a fact that the majority of the arbitrators are male. However, many arbitration institutions in Italy are committed to reducing the gender gap. For instance, CAM in 2016 signed the Equal Representation in Arbitration ‘Pledge’. The Pledge seeks to increase, on an equal opportunity basis, the number of women appointed as arbitrators to achieve a fair representation as soon practically possible, with the ultimate goal of full parity; and

- age. This is often linked, at least in the parties' expectations, to the arbitrator’s experience and competence, although a generational change may ensure a pluralism of values and points of view.

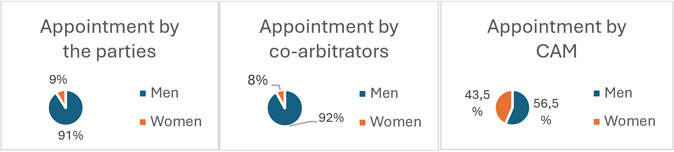

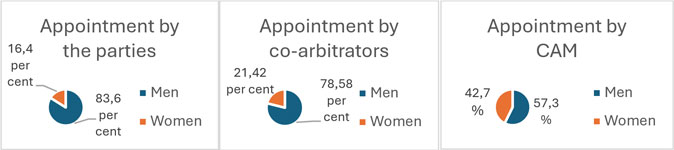

CAM statistical data demonstrates that the institution is sticking to its commitment under the Pledge. Indeed, in 2022 and in 2023, almost one arbitrator out of two appointed by CAM was a woman and, over the same time span, women appointments by parties or co-arbitrators have also significantly increased.[3]

2022

2023

Interim measures

One of the most significant changes introduced by the Reform relates to the arbitrators’ power to adopt interim measures.[4]

Before the Reform, arbitrators had the express prohibition to grant attachments or other precautionary measures and the lack of such power placed Italian Arbitration Law in a minority position as, to the contrary, most jurisdictions allowed arbitrators to provide interim relief.[5]

Indeed, under the previous regime, notwithstanding the presence of an arbitration clause, the parties could obtain interim measures only from state courts, with the limited exception related to corporate arbitration whereby arbitrators had the power by interim decision to suspend a corporate resolution challenged before them.

Following the Reform, article 818(1) ICCP now provides that ‘The parties, by means of the arbitration agreement or a written act prior to the initiation of the arbitration proceedings, including by reference to arbitration rules, may grant the arbitrators the power to issue interim measures. The arbitrators’ competence on interim measures is exclusive’.

From the onset, the wording adopted is extremely clear: arbitrators are allowed to grant interim relief insofar as the parties:

- have specifically entrusted them with said power, either in the arbitration clause or in a written agreement executed before the commencement of the proceedings; and

- have agreed that the proceedings shall be subject to the rules of an arbitration institution that confers said power to the arbitrators (for example, CAM or ICC Rules).

As the new regime applies to proceedings commenced after 1 March 2023, issues have arisen with respect to arbitration clauses entered into before the said date, which refer to arbitration rules.

There are opposite positions in this regard: some commentators believe that the applicable discipline should remain the one current at the time of the execution of the arbitration clause.[6] Others are of the opinion that arbitration proceedings should be governed by the rules in force at the time of their commencement.[7]

The Tribunal of Milan in a recent interim decision (4 January 2025, interim order issued in case 18058/2024) followed the first position: by valuing the intention of the parties, the Tribunal ruled out the power of the arbitrator to adopt interim measures because such power was not provided in the institutional arbitration rules in force at the time of the execution of the arbitration clause (pre-2023) although the same rules were subsequently amended to include it. It is to be seen whether this will remain an isolated decision.

The new regime still leaves room for the intervention of ordinary courts: indeed, pursuant to article 818(2) ICCP, ‘Prior to the acceptance of the sole arbitrator or the establishment of the arbitral tribunal, the request for interim measures shall be filed before the competent court ….’.

This said, as several arbitration institutions have adopted the emergency arbitrator procedure, the choice in the arbitration agreement to be bound to the rules of said institutions should be interpreted as the parties’ common intention that interim relief is granted directly by the emergency arbitrator. As such, ordinary courts could in principle retain competence only until the appointment of the emergency arbitrator.

Interim relief, which may be granted even ex parte, shall be rendered by means of a court order (ordinanza), which can be revoked by the arbitrator.

Pursuant to article 818-bis ICCP, the interim relief measures may be challenged, within 15 days from their adoption by the arbitrator, ‘before the court of appeal of the district where the seat of arbitration is located, on the grounds set forth in the first paragraph of article 829, insofar as compatible, and on the ground of contrariety to public policy’.

This remedy has seen some criticism as commentators have opposed the fact that it would not be possible to obtain, before the competent court of appeal, a new evaluation of the facts, differently from what occurs when challenging an interim relief measure rendered by an ordinary court.[8]

Finally, pursuant to article 818 ter ICCP, the execution of interim measures ‘shall be carried out under the supervision of the court of the district where the seat of arbitration is located or, if the seat of the arbitration is not in Italy, the court of the place where the interim measure must be implemented’.

Corporate arbitration

One of the special types of arbitration under Italian law is corporate arbitration, an arbitration procedure specifically designed for disputes between shareholders, or concerning the management of a company.

Before Cartabia Law, corporate arbitration was governed by Legislative Decree No. 5/2003 (the Corporate arbitration decree) and, in particular, by its articles 34 to 37.

Following the Reform, the legislator has intervened on the rules regarding corporate arbitration by incorporating the rules of the Corporate arbitration decree into the ICCP and, thus, adding to it the new Chapter VI-bis, headed ‘On Corporate Arbitration’.[9]

Preliminarly, it is worth remembering that arbitration clauses contained in companies’ bylaws must specify that the appointment of arbitrators should be made by someone external to the company; otherwise, the clause is void (this applies even in the case of an irregular arbitration – see below). The Italian courts have recently been called upon to address this issue several times.[10]

This said, one of the most significant developments regarding corporate arbitration is the expansion of the arbitrators’ powers to adopt interim measures in corporate matters. The new article 838-bis ICCP refers to the provisions of article 818 ICCP that now allows the parties to an arbitration agreement to grant arbitrators the authority to issue any type of interim measure.

Under the previous regime of corporate arbitration, arbitrators were exceptionally granted only the power to suspend a corporate resolution challenged before them, while ordinary courts retained jurisdiction to issue interim measures other than suspension.

Thanks to the Reform, whereas arbitrators are still empowered by the law, when the conditions for suspension are met, to suspend a corporate resolution regardless of any specific provision in the arbitration clause, they now have the capacity to adopt additional interim measures insofar as the same are bestowed upon them in the statutory clause, which must be drafted in accordance with the rules and limits set out in article 838-bis ICCP.

In this regard, as already seen with reference to ordinary arbitration, there is no reason to exclude, also in the context of corporate arbitration, the application of article 818 ICCP first paragraph with the consequence that the jurisdiction conferred on arbitrators by the arbitration agreement must be exclusive: parties are prohibited from providing for concurrent jurisdiction between ordinary courts and arbitrators.[11]

Similarly, it remains established that, before the arbitrators’ acceptance, also in light of the reasons of urgency put forward by the applicant to request the adoption of an interim measure within a short timeframe, an interim measure may be requested from the ordinary court, which retains jurisdiction even if, in the meantime, the arbitral tribunal has been constituted.[12] It would indeed be unreasonable if, following the arbitrators’ acceptance and the constitution of the arbitral tribunal, the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts would be denied: a similar result would represent a hurdle instead of the simplification intended by the Reform.

The Reform has also introduced the possibility of appealing before the Court of Appeal an arbitral decision suspending a shareholders’ resolution, a remedy previously absent. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the appeal procedure follows the provisions of article 818-bis ICCP.

Irregular Corporate Arbitration

One of the most debated topics, which warrants separate mention, is the admissibility of irregular corporate arbitration.

This is a practical and not just a theoretical issue since there are countless statutory arbitration clauses that provide for an irregular or ‘free’ arbitration process. Although this statistic has been made on a rather limited sample of bylaws, it has been found that approximately one-third of the bylaws in a sample of companies examined contained clauses for irregular arbitrations.[13]

Under the previous version of article 35 of the Corporate arbitration decree, the prevailing doctrinal and jurisprudential opinion supported the admissibility of such irregular corporate arbitration.

The introduction of the new article 838-ter, paragraph 4 ICCP did not change said opinion. Indeed, it has been affirmed that the absence of the phrase ‘also non-ritual’ in the text of such article does not lead to the conclusion that the choice of irregular arbitration is inadmissible, since the general rule set out in article 808-ter ICCP – according to which arbitration is ritual unless expressly stated otherwise in the arbitration agreement – still applies.[14]

Moreover, other arguments apply in favour of the validity of irregular corporate arbitration. First, there are currently numerous statutory clauses for irregular arbitration, and an interpretative approach that seeks to annul such clauses would undermine their validity and applicability with the consequent problems that such an interpretation might lead to. In addition, the Italian legislator entrusted the government with the task of reorganising the matter without narrowing the scope of arbitration competence already established under the previous regulation.

It is therefore clear that the Reform has in no way intervened on the discipline of such irregular arbitration, leaving the significant inadequacy of the framework established by the legislator in 2003 unchanged.

Conclusions

The changes introduced by the Reform concerning corporate arbitration provide an opportunity to reflect on its regulatory framework and applicability. To date, the tool has seen limited success: the number of corporate arbitration requests has been significantly lower than that of ordinary corporate Court litigation. Statistics from a dated case study conducted by Assonime shows that from 2003 to July 2016, 1,597 arbitration requests were filed, concerning 1,322 companies.[15] This is a low number if compared to the number of active companies (both limited liability companies and joint-stock companies) in Italy during that period, which totaled 836,283 as of 31 December 2014. Although more up-to-date data are lacking, it can nonetheless be assumed that companies made an insufficient use of corporate arbitration.[16]

It can be said that a valid opportunity has been wasted because corporate arbitration offers a valuable tool to lighten the judicial system and support the economy, offering companies a faster and more specialised solution for resolving disputes, with effects equivalent to those of a civil judgment.

Even in its international dimensions, corporate arbitration can be an effective tool for creating a legal system that is favourable to businesses and competitive in attracting investments, including foreign ones. However, to be truly effective, its regulation must be clear and well-structured, with procedures that are easy to interpret. In this regard, the provision introduced by Cartabia Law do not appear to bring about significant change in this regard, as the legislator has not seized the opportunity to address the main interpretative issues surrounding this special form of arbitration.

Challenge to awards and enforcement

Arbitral awards can be challenged in Italy for nullity, a remedy that has to be introduced before the Court of Appeal of the district where the arbitration had its seat within 90 days from the notification of the award or six months from the date of its last signature.

Under article 829 ICCP, awards may be challenged on 12 procedural grounds notwithstanding any prior waiver whereas, only if expressly provided by law or the parties themselves, the request for nullity may be introduced based on a violation of the legal provisions governing the merits of the dispute. The review of the motivation is fairly limited to cases of serious lack thereof, and errors in law are a reason for challenge only if expressly provided by the parties or by specific legal provisions. Decisions contrary to public policy can always be challenged without restrictions.

Pursuant to article 831 ICCP, arbitral awards may also be challenged through revocation, an extraordinary mean applicable in very limited cases such as fraud or forgery of one party against the other, and third party opposition, a remedy open to third parties demonstrating that the award affects their rights or to creditors that establish that the decision has been the result of a fraud carried out to their detriment; third party opposition appears to be a rather specific feature of Italian arbitration law. Under article 825 ICCP, the party seeking enforcement of an award rendered by an arbitral tribunal seated in Italy has to file its request before the registry of the tribunal of the district where the arbitration had its seat, submitting the original or a certified copy of the award. Following an assessment of the formal validity of the award, the competent court shall declare the same enforceable by decree and shall inform the parties of the decision, which may be challenged before the Court of Appeal within 30 days from the communication.

Enforcement of a foreign award, disciplined by article 839 ICCP, is to be requested before the President of the Court of Appeal of the district where the other party resides; should that party not be resident in Italy, jurisdiction shall be retained by the Court of Appeal of Rome. Following the Reform, upon assessment of its formal validity, the President shall declare by decree the immediate enforceability of the foreign award, unless the subject matter of decision was not arbitrable under Italian law or the decision itself includes provisions contrary to public policy.

The presidential decree may be opposed within 30 days from its notification before the Court of Appeal, which, if the existence of serious grounds is demonstrated by the opposing party, is empowered to stay the enforceability or the enforcement of the award. Said remedy may also be adopted, possibly upon the presentation of appropriate security, by the Court of Appeal if the opposing party has already requested the annulment or suspension of the foreign award before the competent authority.

Case law highlights

Italian Supreme Court, decision No. 26600 of 14 October 2024

This decision, rendered by the Joint Sections of Supreme Court, is the result of an appeal for a ruling on jurisdiction brought by two shareholders of a company named Petrolvalves SpA; the applicants, who had sold 40 per cent of Petrolvalves' shares in 2016, had been sued in London-seated ICC arbitration proceedings by Petrolvalves, which had been the target of an acquisition and – as a consequence of the merger between the buyer and the target itself – was the successor of the rights of the acquiring company.

During the arbitration proceedings – because of the indemnification obligations deriving from the share purchase agreement – the selling shareholders were requested compensation of €82 million for damages suffered by the company and resulting from the ascertainment of acts of corruption committed by former employees of the same, and subject to a plea bargain of the penalty during the criminal proceedings.

While the arbitration proceedings were pending, the selling shareholders instituted a separate proceeding before the Court of Milan, suing Petrolvalves (plaintiff in the arbitration proceedings) and its directors, challenging the 2021 financial statements, arguing their invalidity, and requesting that the company and the directors be ordered to pay damages. In the course of those proceedings, Petrovalves brought a counterclaim against the selling shareholders on the basis of their liability as heirs of a former director of the company.

During the proceedings before the Court of Milan, the selling shareholders promoted a preventive ruling on jurisdiction; thus, they requested the Court of Cassation to ascertain the exclusive jurisdiction of the Court of Milan in relation to the claims for damages brought by Petrolvalves in arbitration; they claimed the identity of the requests filed by Petrolvalves before the ICC arbitration panel and as a counterclaim before the Court of Milan; they asked the Court to ascertain the derogation from the jurisdiction of the ICC arbitral tribunal and the nullity of the arbitration clause. In particular, the shareholders argued that the declaration of nullity of the arbitration clause would fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the national court.

The recourse brought by the selling shareholders was rejected by the Joint Sections of the Court of Cassation, which declared it inadmissible.

The Supreme Court held that the preventive ruling on jurisdiction had been introduced to surreptitiously obtain from the Court a decision on the arbitral competence, with reference to the arbitration introduced by Petrolvalves against the selling shareholders even before the filing of the proceedings before the Court of Milan.

The Court then applied the principles contained in articles 817 and 819 ter ICCP to reaffirm the principle of Kompetenz Kompetenz (ie, the exclusive competence of the ICC arbitral tribunal to decide on the validity of the arbitration clause and on its own jurisdiction).

The Court has, thus, clearly ruled that during the course of arbitration proceedings, no claims may be brought before the Italian domestic courts to assert the invalidity or ineffectiveness of the arbitration clause, since any related question is at this stage referred to the arbitrators, whose decision can be challenged only by means of the normal remedies that can be proposed against the arbitration award.

Italian Supreme Court, decision No. 15861 of 6 June 2024

In this decision, the Joint Sections have dealt once again with the issue of the arbitral clause – providing for the jurisdiction of an international arbitral tribunal (a Singapore arbitral tribunal) – included in a contract by generic reference to the general conditions of contract (clause ‘per relationem’), and without an express and specific reference to the arbitral clause: the Court has thus re-affirmed the invalidity of such a clause, in line with its precedent ruling No. 11529 of 2009.

The decision seems, however, not entirely satisfactory, as it has not given a specific ruling to the question (which had indeed been raised by the appellants, but was discarded as irrelevant due to lack of an actual interest) of the choice of the law to be applied to the matter of the validity of the arbitral clause, which seemed relevant considering that the two connected contracts at stake were governed by Chinese and Malaysian law and it therefore seems disputable to decide the issue based on Italian law (and not on the contract law or on the lex arbitri). A specific motivation on this vexed issue would have been beneficial. On another relevant aspect, the Court has qualified here the issue of the validity of the arbitral clause providing for a foreign arbitration as an issue of jurisdiction and not of competence.

Italian Supreme Court, decision No. 9429 of 9 April 2024

A US company, holder of a European patent on a seedless red grape, entered into a lease agreement with an Italian company, owner of a land, granting it, for a fee, the licence to rent and cultivate the buds of such seedless red grape. The contract provided that the fruit produced by such buds was to be marketed by a distributor authorised by the US company.

Although according to the Italian grower, the annual harvest was compromised by heavy flooding and the unavailability of the authorised distributor to harvest in time, the US company terminated the contract for non-performance and for the breach of the exclusivity clause.

The arbitral tribunal has admitted the claim filed by the US company and declared the termination of the contract due to the grower’s non-fulfillment of its obligations. The Italian company challenged the award before the Court of Appeal and, then, before the Court of Cassation. In particular, the grower objected that the exclusivity clause was contrary to public policy and, specifically, to the EU's founding principles of protecting competition and safeguarding agricultural production. The Court of Cassation clarified that the public policy referred to in article 829 of ICCP coincides with the fundamental rules and principles of the Italian legal system, to which the precepts of international law, both general and covenant, and EU law – specifically, EU law principles protecting the public interest of agricultural production – must be added. The Supreme Court granted the appeal and referred the case back to the Court of Appeal of Milan, which will judge the case on the basis of the aforementioned principle of law. The case therefore is still pending on the merits.

Italian Supreme Court, decision No. 16124 of 11 June 2024 and Court of Appeal of Genoa, decision No. 650 of 9 July 2020

The case concerned an individual who appealed before the Court of Cassation against the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Genoa (No. 650 of 9 July 2020) that rejected the objection he had lodged pursuant to article 840 ICCP (opposition) against the exequatur decree ex article 839 ICCP by which the President of that Court had declared effective in Italy the final award pronounced by a Geneva arbitral tribunal in a dispute concerning the liability of the administrative bodies of an Italian joint-stock company of which the claimant was a shareholder.

Indeed, according to the claimant, the arbitration clause provided in the bylaws was null and void as it was contrary to mandatory provisions of Italian law, specifically articles 34, 35 and 36 of the Corporate arbitration decree, which sets out the limits and rules under which an Italian arbitration clause should be drafted. In this case, the arbitration clause in the bylaws stated that the applicable law would be Italian law and that the seat of the arbitration would be in Switzerland, in Geneva, and argued the invalidity of the arbitration clause on these grounds, alleging that an arbitration clause included in the bylaws of a company cannot defer corporate disputes to a foreign arbitral tribunal.

The Genoa Court of Appeal had previously upheld the validity of the arbitration clause based on the following arguments:

- the arbitration clause that gave rise to the arbitration proceeding allowed, as explicitly indicated by the parties in the arbitration clause, for a distinction between the substantive law applicable to the merits (Italian law in the case at stake) and the procedural law corresponding to the seat of arbitration (Swiss law in the case at stake);

- the validity of the arbitration agreement, being an act of substantive law, must be assessed solely under the substantive rules of the legal system chosen by the parties, which was Italian law. The arbitration clause was therefore valid according to Italian substantive law. The claimant, however, sought to apply Italian procedural law to the arbitration agreement, thereby seeking its nullity by confusing the Italian substantive rules governing the validity of the arbitration clause in the bylaws (relevant for determining the validity of the arbitration clause) with the Italian procedural rules regarding domestic corporate arbitration proceedings (which are irrelevant, as the arbitration leading to the final award was governed by Swiss procedural law); and

- articles 34, 35 and 36 of the Corporate arbitration decree (now, as a consequence of the Reform, incorporated into articles 838-bis ff ICCP) deal merely with the appeals against domestic awards issued as a result of arbitration proceedings held solely in Italy pursuant to article 816 ICCP, and is not applicable to foreign awards.

The Civil Court of Cassation in its interlocutory decision of 11 June 2024, has decided to refer the issue to the public hearing considering the particular complexity of the matter, which has been subject to conflicting opinions in the absence of specific legal precedents.

A decision is still pending and this crucial issue at the intersection between Italian domestic corporate arbitration provisions and international arbitration principles is therefore unsettled so far.

Endnotes

[1] Quaderni di Economia e Finanza, nr 715- October 2022: ‘La giustizia civile in Italia: durata dei processi, produttività degli uffici e stabilità delle decisioni’, https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2022-0715/QEF_715.pdf.

[2] Alberto Beretta, Gabriele Scuratti, Francesca Guazzugli Marini, ‘PWC/CAM Rapporto sulla consulenza tecnica in arbitrato’, Milan, September 2024.

[3] 8 MARZO: DIVARIO DI GENERE E PROFESSIONI LEGALI, in https://www.camera-arbitrale.it/upload/documenti/Comunicati per cent20stampa/2023/Nomine per cent20donne per cent20Arbitro per cent20marzo per cent202023.pdf.

[4] Report annuale arbitrato 2024, in https://www.camera-arbitrale.it/upload/documenti/statistiche/2023/arbitrato per cent20cam per cent20dati per cent202023.pdf.

[5] F. Corsini ‘I poteri cautelari degli arbitri ai sensi del nuovo art. 818 c.p.c.’, Rivista di Diritto Processuale n. 3, 1 July 2023, p. 866

[6] Op. cit.

[7] L. Salvaneschi, ‘I poteri cautelari degli arbitri’, Rivista dell’arbitrato, 4/2023, pp. 829-849

[8] Op. cit.

[9] Chapter VI bis largely incorporates, under articles 838-bis, 838-ter, 838-quater, and 838-quinquies, the provisions already contained in articles 34 to 37 of the Decree in https://www.camera-arbitrale.it/upload/documenti/centro per cent20studi per cent20normativa/cpc-ENG.pdf.

[10] Supreme Court of Cassation, 5 June 2023, No. 15700, in DeJure; Milan Court, 24 March 2023, No. 2412, in DeJure.

[11] R. Rordorf, ‘L’arbitrato societario dopo la “riforma Cartabia” (D.Lgs. n. 149/2022)’, p. 3, Le Società, n. 11, 1 November 2023, p. 1285.

[12] Op. cit.

[13] “L’arbitrato societario nella prospettiva delle imprese”, Note e studi 5-2017, in https://www.assonime.it/attivita-editoriale/studi/Pagine/noteestudi5-2017.aspx.

[14] F. Corsini, ‘L’arbitrato societario dopo la riforma’, p. 54, Rivista dell’arbitrato 1/2024, pp. 45 – 72.

[15] “L’arbitrato societario nella prospettiva delle imprese”, https://www.assonime.it/attivita-editoriale/studi/Pagine/noteestudi5-2017.aspx.

[16] G.D. Mosco, “L’arbitrato societario nella legge Cartabia”, Giurisprudenza Commerciale, fasc.5, 1 October 2023, pp. 735- 756.