The pursuit of investment treaty arbitration by Asia-Pacific investors

This is an Insight article, written by a selected partner as part of GAR's co-published content. Read more on Insight

In summary

In this article, we survey the manner in which Asia-Pacific investors have been increasingly turning to investment treaty arbitration to seek remedies for their foreign investment losses. We identify the nationality of Asia-Pacific investors that have pursued claims, the industries concerned, the states targeted, the treaties utilised, the impugned state actions and the outcomes of claims. As we illustrate, a diverse range of Asia-Pacific investors have now pursued investment treaty claims against states worldwide across a variety of industries. Despite the increased use of investment treaty arbitration by Asia-Pacific investors, they have brought a disproportionately low number of investment claims, with almost half of cases targeted against Asia-Pacific states.

Discussion points

- At least 84 investment treaty arbitrations have been pursued by Asia-Pacific investors against 49 states worldwide

- 70 investment treaties have been utilised by Asia-Pacific investors across these 84 investment treaty arbitrations

- The highest number of investment treaty arbitrations have been pursued by investors from China, India, South Korea, Singapore and Australia. No investment treaty arbitrations have been pursued by investors from several of the region’s major developing economies, including Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam

- Claims relating to investments in the construction, energy, mining and financial services sectors have been most frequently pursued by Asia-Pacific investors

Referenced in this article

- JGC Holdings Corporation (formerly JGC Corporation) v Kingdom of Spain

- Itochu Corporation v Kingdom of Spain

- Mitsui & Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Spain

- Nissan Motor Co, Ltd v Republic of India

- Macro Trading Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China

- MTD Equity Sdn Bhd and MTD Chile SA v Chile

- Kenon Holdings Ltd and IC Power Ltd v Republic of Peru

- Ping An Life Insurance Company of China, Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Limited v Kingdom of Belgium

- White Industries Australia Limited v The Republic of India

- Tethyan Copper Company Pty Limited v Islamic Republic of Pakistan

- Beijing Urban Construction Group Co Ltd v Republic of Yemen

Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been instrumental for economic development in the Asia-Pacific region. In a bid to attract FDI, Asia-Pacific states have modernised their laws and policies governing foreign investment. This has included embracing bilateral investment treaties (BITs), which are intended to encourage cross-border investment by extending various protections to foreign investments. These protections include promises of non-discrimination, fair and equitable treatment, security and protections against expropriation. Typically, BITs also grant foreign investors the right to bring their claims directly against host states through investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms.[1]

Over time, the rising global economic prominence of the Asia-Pacific has also seen the region emerge as a major source of outbound FDI.[2] Several Asia-Pacific states are now significant capital exporters. BITs and multilateral arrangements entered into by Asia-Pacific states are aimed not only at enticing inbound FDI, but also at protecting outbound FDI by protecting the foreign investments of their nationals. Inevitably, this has led to Asia-Pacific investors invoking ISDS, when available as a dispute resolution mechanism, to seek remedies in respect of investment losses suffered in host states.

In this article, we survey the manner in which Asia-Pacific investors have been increasingly turning to investment treaty arbitration to seek relief in respect of their foreign investments. We identify the nationality of Asia-Pacific investors that have pursued claims, the industries concerned, the states targeted, the treaties utilised, the impugned state actions and the outcomes of claims.

The statistics are striking. A diverse range of Asia-Pacific investors have now pursued investment treaty claims across a variety of industries, and against states worldwide. Despite the increased use of investment treaty arbitration by Asia-Pacific investors, they have brought a disproportionately low number of investment treaty arbitrations as compared to investors from other regions.

We base our analysis on the Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator repository, which was first released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in February 2021 and most recently updated in July 2023.[3] This useful resource contains a wealth of information on all known treaty-based investor-state arbitrations. As some of these arbitrations can be kept fully confidential, there are likely to be other treaty-based investor-state arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors that are not included in the repository and, therefore, not identified in our analysis.[4]

Asia-Pacific investors pursuing investment treaty arbitration

In this section, we consider statistics regarding investment treaty claims brought by investors from the Asia-Pacific region.

As it happens, the Asia-Pacific region was the birthplace of investment treaty arbitration. In 1987, a Hong Kong investor commenced the first-ever investment treaty arbitration in Asian Agricultural products Ltd v Sri Lanka.[5] This followed the Sri Lankan government’s destruction of the investor’s shrimp farming property through raids on suspected Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam hideouts. The investor succeeded in persuading the majority of an International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) tribunal that the Sri Lankan government had violated its obligations to protect and secure its investments pursuant to the BIT between Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom. The Hong Kong investor was protected under the terms of that treaty as, at that time, Hong Kong was a territory of the United Kingdom and the BIT had been extended to Hong Kong.[6]

Despite the Hong Kong investor’s success in this first case, between 1987 and 1999, no investment treaty arbitrations were commenced by Asia-Pacific investors. In fact, it was only six years after the Hong Kong investor’s commencement of its claim against Sri Lanka that the next investor commenced the second-ever investment treaty arbitration in 1993 in AMT v Democratic Republic of the Congo.[7] This case related to two episodes in which soldiers of the (then) Zairian armed forces destroyed, damaged or carried away property, finished goods and other valuable objects belonging to a local subsidiary of the investor. The Tribunal found violations of the DR–Congo–United States BIT by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and awarded damages to the investor.[8]

There was a slow global uptick in investment treaty arbitrations during the 1990s. During that decade, investors commenced a total of 43 investment treaty arbitrations, the majority of which were commenced in 1998 (11 cases), and 1999 (14 cases).[9] Malaysia was the only Asia-Pacific state to face investment treaty arbitrations during the 1990s, both of which were pursued by the same investor.[10]

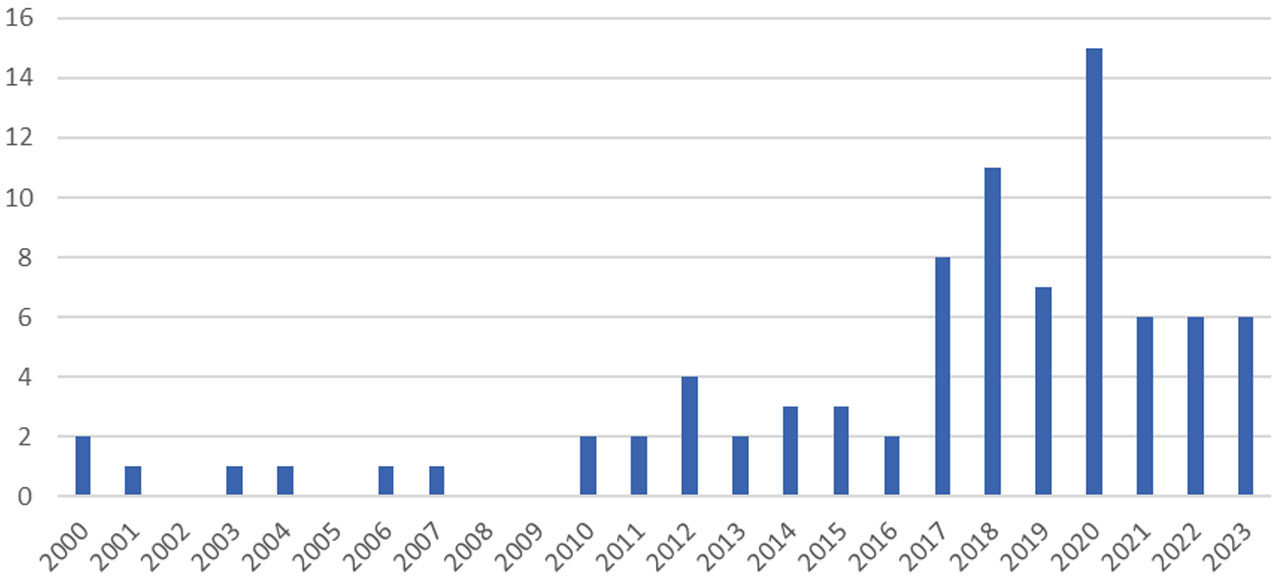

Since the turn of the millennium, the number of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors has gathered pace. Table 1 sets out the number of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by investors from the Asia-Pacific region from 1 January 2000 until 31 July 2023.[11]

Table 1: Investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors (2000–2023)

The first cases brought by Asia-Pacific investors were Ashok Sancheti v Germany and Yaung Chi OO Trading Pte Ltd v Myanmar.[12] Details about Ashok are scarce (including the reasons for its discontinuance and whether it resulted in settlement), but more is known about Yaung Chi,[13] which concerned the alleged expropriation of the Singaporean investor’s brewery in Myanmar. The investor alleged that there were multiple armed seizures of the brewery, and that some of its bank accounts were frozen. The tribunal dismissed the claim on jurisdiction, finding that the investor did not qualify for protection as the investment was not approved in writing by Myanmar after the ASEAN Agreement had come into force for Myanmar.[14]

Between 2000 and 2016, a steady trickle of cases were brought by Asia-Pacific investors, averaging at just 1.5 cases a year. A leap occurred in 2017 and 2018, which saw eight and 11 cases respectively. In 2020, the number of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors peaked with a record 15 cases, before declining to six cases in each year from 2021 onwards.

Review of the 15 cases brought in 2020 reveals that the cases were unrelated to each other. They were brought under 14 different investment treaties against 13 states,[15] with three claims brought by investors against China.[16] It remains to be seen whether 2020 represents the high watermark of, or is reflective of a continuing general upward trend in, investment treaty arbitrations brought by Asia-Pacific investors.

The number of claims lodged by investors from the Asia-Pacific region does not make up a large proportion of global cases. As of 31 July 2023, 1,303 (known) investment treaty arbitrations had been commenced, with only 84 brought by Asia-Pacific investors. This means that Asia-Pacific investors have commenced just over 6 per cent of the total number of known investment treaty arbitrations worldwide. This is despite Asia-Pacific investors contributing around 36 per cent of global outward FDI in 2022.[17] In the third quarter of 2023, Japan and China were two of the top three sources of FDI outflows worldwide (US$60 billion and US$53 billion respectively).[18] In this light, Asia-Pacific investors have brought a disproportionately low number of investment treaty arbitrations.

Table 2 sets out the nationalities of the Asia-Pacific investors that brought investment treaty claims between 2000 and 2023.

Table 2: Investment treaty arbitrations by nationality of investor (2000–2023)

| Nationality of investor | Number of arbitrations |

|---|---|

| China | 21 |

| India | 12 |

| South Korea | 11 |

| Singapore[19] | 11 |

| Australia[20] | 10 |

| Malaysia | 9 |

| Japan | 6 |

| Hong Kong | 3 |

| Macao | 1 |

By a significant margin, Chinese investors have been the most frequent claimants (with 21 cases), followed by claims brought by Indian investors (12 cases), South Korean investors (11 cases) and Singaporean investors (11 cases).

Claims by Chinese investors have not been concentrated against any single state. With the exception of Vietnam (against which two separate cases were commenced by the same Chinese investors),[21] all other states have only been targeted once to date. These states are Belgium,[22] Cambodia,[23] the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[24] Ecuador,[25] Finland,[26] Ghana,[27] Greece,[28] South Korea,[29] Laos,[30] Malta,[31] Mexico,[32] Mongolia,[33] Nigeria,[34] Peru,[35] Saudi Arabia,[36] Sweden,[37] Trinidad and Tobago,[38] Ukraine[39] and Yemen.[40] This wide range of states across Africa, the Asia-Pacific, Europe, North and South America, is illustrative of the breadth of Chinese FDI globally.

A similar picture emerges when considering claims pursued by Indian investors against host states. Indian investors have twice pursued claims against Bosnia and Herzegovina[41] and North Macedonia,[42] with single cases pursued against Germany,[43] Indonesia,[44] Libya,[45] Mauritius,[46] Mozambique,[47] Poland,[48] Saudi Arabia[49] and the United Kingdom.[50]

Likewise, South Korean investors have targeted a wide variety of states. Other than two cases against Vietnam, [51] all other investment treaty arbitrations pursued by South Korean investors have been one-offs, with claims pursued against China,[52] India,[53] Kyrgyzstan,[54] Libya,[55] Nigeria,[56] Oman,[57] Peru,[58] Saudi Arabia[59] and the United States.[60]

Australian investors have never targeted the same state twice, with claims pursued against Egypt,[61] Georgia,[62] India,[63] Indonesia,[64] Mongolia,[65] Pakistan,[66] Papua New Guinea,[67] Poland,[68] Sweden[69] and Thailand.[70]

Singaporean investors have been slightly more consistent in their approach, with investment treaty arbitrations twice pursued against Australia,[71] China[72] and Indonesia,[73] with single cases pursued against Mexico,[74] Myanmar,[75] Peru,[76] Taiwan[77] and Turkey.[78]

In light of Japan’s significant FDI outflow, it is notable that Japanese investors have only pursued six known investment treaty arbitrations. It was only in 2015 that the first investment treaty arbitration was commenced by a Japanese investor, when JGC Holdings Corporation pursued and ultimately prevailed in claims against Spain following the government’s imposition of measures affecting the renewables sectors, including a tax on power generators’ revenues and a reduction in subsidiaries for renewable energy producers.[79] In 2016, Eurus Energy Holdings Corporation brought and ultimately succeeded in claims against Spain arising out of the same measures.[80] In 2018, Itochu Corporation also commenced a case against Spain in respect of these measures, with the proceedings currently pending.[81] In 2020, Mitsui filed a claim against Spain in relation to a solar power project, alleging that Spain’s new renewables incentives regime violates the Energy Charter Treaty.[82] This case also remains pending. Other cases pursued by Japanese investors included Nissan’s claims against India for non-payment of incentives promised under an agreement for the building of a car plant (which ultimately settled),[83] and Macro Trading Co Ltd’s claim against China filed in 2020, the details of which are not publicly available.[84]

It is notable that investors from developing economies of the Asia-Pacific region are not typically pursuing investment treaty claims. No known claims have been pursued by investors from significant developing economies in the region, including Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. The explanation for this (at least in part) is likely that net FDI outflows for each of these states are comparatively significantly lower than many states whose investors have pursued investment treaty claims.[85]

Table 4 sets out the industries of the Asia-Pacific investors behind the 84 investment treaty arbitrations commenced between 2000 and 2023.

Table 4: Investment treaty arbitrations by industry of investor (2000–2023)

| Industry of investor | Number of arbitrations |

|---|---|

| N/A (Individuals) | 13 |

| Construction | 13 |

| Mining | 13 |

| Financial and insurance services | 11 |

| Energy | 9 |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Manufacturing | 5 |

| Information and communications | 4 |

| Real estate | 3 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 3 |

| Transport and storage | 1 |

| Automotives | 1 |

| Retail | 1 |

As Table 4 reveals, investors from a variety of industries have commenced investment treaty arbitrations. The highest concentrations of investors have been from the mining sector (15 per cent), construction sector (15 per cent), financial services sector (13 per cent) and energy sector (11 per cent). These figures bear some similarity to the global data,[86] with the highest number of investment treaty arbitrations worldwide brought by investors from the energy sector (17 per cent), mining sector (16 per cent), manufacturing sector (16 per cent), construction sector (11 per cent) and real estate sector (5 per cent). Combined, investors from the mining, energy, manufacturing and construction sectors have pursued the majority of cases (57 per cent globally and 48 per cent in the Asia-Pacific region).

States targeted and treaties invoked by Asia-Pacific investors

The statistics reveal that Asia-Pacific investors most frequently target Asia-Pacific states. Of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors, approximately 44 per cent have been targeted against Asia-Pacific states. Four of the top five states targeted were Asia-Pacific states, namely China (five cases),[87] Indonesia (four cases),[88] India (four cases)[89] and Vietnam (four cases).[90] The second most-targeted state was Spain (four cases),[91] albeit all of these instances concerned claims pursued by Japanese investors following the change in Spain’s renewables tariff policy.[92]

Other Asia-Pacific states targeted by Asia-Pacific investors include Laos[93] and Australia[94] (three cases each), South Korea[95] and Mongolia[96] (two cases each), and a single case against each of Cambodia,[97] Japan,[98], Kyrgyzstan,[99] Myanmar,[100] Pakistan,[101] Papua New Guinea,[102] the Philippines,[103] Sri Lanka,[104] Taiwan[105] and Thailand.[106]

In an earlier study, we surveyed all investment treaty arbitrations commenced against Asia-Pacific states (by investors worldwide) between 1987 (when the first-ever investment treaty arbitration was commenced) and mid-2022.[107]

We noted that many states across the Asia-Pacific region had faced investment treaty arbitration. These included India (29 cases), Pakistan (12 cases), South Korea (10 cases), Vietnam (nine cases), China (eight cases), Indonesia (eight cases), Mongolia (six cases), Philippines (six cases), Sri Lanka (five cases), Laos (four cases), Malaysia (three cases), Australia (two cases), Thailand (two cases), and a single case faced by each of Bangladesh, Cambodia, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Nepal, Papua New Guinea and Taiwan.[108] Only a minority of Asia-Pacific states had not yet faced any investment arbitrations including, most prominently, New Zealand and Singapore.

We also observed that the number of investment treaty arbitrations faced by Asia-Pacific states was perhaps not as high as might have been expected. As at 31 July 2022, there had been 1,230 known investment treaty arbitrations worldwide, but only 111 of these (9 per cent) were commenced against Asia-Pacific states. The region accounts for 60 per cent of the world’s population[109] and its share of global gross domestic product has continued to grow, representing 64 per cent of global GDP growth for the past decade, with the region now accounting for 44 per cent of global GDP.[110] Asia-Pacific states have entered into over 700 BITs. Seen in this light, Asia-Pacific states have faced a disproportionately low number of investment treaty arbitrations.

Equally notable is that of the 84 known investment treaty arbitrations pursued by Asia-Pacific investors, a total of 70 investment treaties have been invoked. The Energy Charter Treaty has been most frequently invoked (seven times).[111] This is in line with the broader global trend, with 162 cases brought under the Energy Charter Treaty.[112] States are looking to withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty, with Russia, Italy, France, Germany, Poland and Australia all having withdrawn; Luxembourg due to leave by mid-2024;[113] and the United Kingdom has recently announced its intention to withdraw.[114]

Other treaties that have been invoked on more than one occasion by Asia-Pacific investors are the China–Laos BIT (three times),[115] and the China–Singapore BIT,[116] ASEAN Investment Agreement,[117] India–North Macedonia IIA,[118] Bosnia and Herzegovina–India BIT,[119] China–Republic of Korea BIT[120] and ASEAN–China Investment Agreement (each of which have been invoked on two occasions).[121]

State action leading to investment treaty arbitration

Table 5 sets out the most common state actions giving rise to investment treaty claims by Asia-Pacific investors.

Table 5: Investment treaty arbitrations by type of state action (2000–2023)

| Type of state action | Number of arbitrations |

|---|---|

| Revocation of or failure to grant or renew licence, concessions or permits | 23 |

| Contract breach, modification or cancellation | 14 |

| Judicial process | 7 |

| Nationalisation | 6 |

| Tax measures | 5 |

| Social protests/civil unrest | 4 |

| Others | 8 |

| Unknown | 17 |

Evidently, a wide range of state measures have been challenged by Asia-Pacific investors. We set out below examples of the five categories of state action that have given rise to the highest number of investment treaty arbitrations.

- Revocation of or failure to grant or renew license, concessions, or permits: MTD v Chile,[122] which was brought by a Malaysian investor against Chile under the Chile–Malaysia BIT, is a case reflective of a fact pattern that often arises in revocation or failed licence cases. Chile had assured the investors that the land secured by them for an investment project (the development of a satellite city) would be rezoned to permit the development to proceed. However, the relevant Chilean governmental agency subsequently refused to rezone the land. The tribunal found that this represented a breach of Chile’s fair and equitable treatment (FET) obligation (where it had created and encouraged expectations that the project would be implemented in the proposed location). The tribunal awarded damages to the investors on the basis of expenditures made in relation to the investment.

- Contract breach, modification or cancellation: Kenon and IC Power v Peru[123] was brought by two Singaporean investors who indirectly owned and operated power plants in Peru. They pursued claims under the free trade agreement (FTA) between Singapore and Peru relating to the modification of a contract by a resolution adopted by the Peruvian regulator of the energy sector. The investors contended that the resolution adopted by the Peruvian regulator fundamentally altered the terms of a tender awarded to their Peruvian subsidiary, causing losses to their investment that they claimed breached the FET and full protection and security standards in the FTA. The tribunal held that the adoption of the resolution was manifestly arbitrary and breached the FET standard, and awarded the investors damages for the losses caused by the issuance of the resolution.

- Nationalisation: there has not yet been a successful claim brought on the basis of nationalisation by an Asia-Pacific investor. There have been two cases in which such claims have been pursued, namely Ping An v Belgium[124] and AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v China.[125]Both cases were dismissed on jurisdictional grounds. Ping An v Belgium was brought by two Chinese investors under the 2009 BIT between the Belgium–Luxembourg Economic Union and China. The investors had jointly become the largest shareholder of the Fortis group. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the Belgian government implemented a series of measures that effectively nationalised the Belgian subsidiary of the group, diluting the investors’ interest in Fortis. The Belgian subsidiary was eventually sold, which the investors alleged resulted in significant loss to their investment. The tribunal declined jurisdiction on the basis that the 2009 BIT did not cover disputes that arose before the BIT entered into force.

- Judicial process: in White Industries v India,[126] judicial delays that left the investor, an Australian mining company, unable to enforce an ICC award for nine years were found to be in breach of India’s obligations in the Australia–India BIT. The tribunal awarded the investor damages, which included the full amount of the underlying ICC award and legal fees incurred in the ICC and subsequent court proceedings.

- Tax measures: Eurus Energy v Spain[127] was brought by a Japanese investor against Spain under the Energy Charter Treaty in response to reforms to Spain’s renewables incentive regime. The investor submitted that the reforms reduced subsidies and imposed a 7 per cent tax on the revenue of renewable power generators, which had the indirect effect of retroactively clawing back subsidies received in the past. The tribunal found that the reforms breached the investor’s legitimate expectation that the subsidies would have continued (in some form) over the lifetime of the wind power projects, and that clawback of the subsidies breached the Energy Charter Treaty’s stability principle.

Outcome of investment treaty arbitrations pursued by Asia-Pacific investors

Table 6 sets out the status and outcome of the 84 known investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors between 2000 and 2023.

Table 6: Status of investment treaty arbitrations (2000–2023)

| Type of government action | Type of government action |

|---|---|

| Pending | 40 |

| State succeeded | 12 (including 8 on jurisdiction) |

| Investor succeeded | 11 |

| Settle | 9 |

| Discontinued for unknown reasons | 7 |

| Discontinued as claimant failed to pay required advances for costs | 3 |

| Content of award undisclosed | 2 |

As Table 6 demonstrates, almost half of the arbitrations brought by Asia-Pacific investors are still pending. This reflects the very recent increase in the number of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors (as set out in Table 1).

In cases that have concluded, the investor or the host state each succeeded in roughly a quarter of cases, with the remainder either settled or discontinued (including because the investor failed to pay the required advances for costs).

Of the determined cases where states succeeded, two-thirds were based on jurisdictional grounds. It is commonplace for states to raise jurisdictional objections to investment treaty claims. Often, proceedings are bifurcated, with a separate jurisdictional phase taking place before the tribunal determines whether the investor’s claims should be heard on the merits. When determining jurisdiction, tribunals will consider whether they have subject matter, personal and temporal jurisdiction. Tribunals need to establish the consent of the host state to submit the dispute to arbitration. The investor must also qualify as a protected investor under the treaty. Its investment must likewise qualify as a protected investment under the treaty and must have been protected at the time of the host state’s alleged breaches of its obligations. The high number of claims dismissed on jurisdictional grounds, highlights the importance of thoroughly assessing jurisdictional arguments before commencing an investment treaty arbitration.

Of the 14 cases determined on the merits, 11 were determined in favour of the investor, revealing that a significant proportion of the cases that cleared the requisite jurisdictional hurdles were judged to be sufficiently meritorious. Where the investor succeeded, awards ranged from US$0.78 million to US$6 billion, with the median value of award in the US$50 million–US$100 million range. In three cases, investors were awarded over US$1 billion.[128]

Conclusion

The rise in the use of investment treaty arbitration has not been driven by Asia-Pacific investors, who have commenced only around 6 per cent of the total number of known investment treaty arbitrations worldwide. This is despite Asia-Pacific investors now contributing around one-third of global outward FDI. In light of this, it seems possible that the proportion of investment treaty arbitrations commenced by Asia-Pacific investors is likely to increase to reflect this contribution. The fact that almost half of investment treaty arbitrations pursued by Asia-Pacific investors were commenced in the past five years alone tends to support this contention.

In recent years, Asia-Pacific states have been focused on developing free trade agreements and multilateral pacts.[129] The most prominent of these are the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The CPTPP and RCEP represent some of the largest free trade areas in the world. The CPTPP provides for ISDS, whereas the RCEP contains an inter-state dispute settlement mechanism, requiring investors to petition home states to bring claims on their behalf against host states. Whilst it remains in its infancy, the CPTPP has already seen a claim pursued by a Canadian investor against Mexico.[130] The CPTPP and the RCEP are likely to impact the use of investment treaty arbitration by Asia-Pacific investors, although it remains to be seen precisely how.

Asia-Pacific investors have pursued investment claims against at least 49 states in total. Chinese investors have been the most active against a wide variety of states, which might be seen to reflect China’s global economic ambitions. In contrast, Japanese investors have brought a disproportionately low number of claims, particularly when compared to Japan’s relatively high FDI output. Investors from leading developing economies, including Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, are yet to bring any claims. As the Asia-Pacific region continues to evolve, and outbound FDI evolves alongside it, we are likely to see Asia-Pacific investors increasingly prominent in this space.

Endnotes

[1] Kenneth J Vandevelde, ‘A Brief History of International Investment Agreements’, 12 UC Davis J Int’l L & Pol’y 157, 171 (2005).

[2] World Bank, ‘Foreign direct investment, net outflows (% of GDP) - East Asia & Pacific’, The World Bank: Data (Web Page). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?locations=Z4.

[3] The Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator is available on the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s website. Its content is currently accurate to 31 July 2023.

[4] We have also supplemented our analysis with additional cases not included in the UNCTAD Repository identified from IA Reporter, Jus Mundi and ICSID.

[5] International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) Case No. ARB/87/3.

[6] The BIT had been extended by the United Kingdom to Hong Kong by virtue of an exchange of notes with effect as of 14 January 1981: see Asian Agricultural Products Ltd v Sri Lanka award, paragraph 1.

[7] American Manufacturing & Trading, Inc v Democratic Republic of the Congo (ICSID Case No. ARB/93/1).

[8] American Manufacturing & Trading, Inc v Democratic Republic of the Congo (ICSID Case No. ARB/93/1).

[9] UNCTAD ISDS Navigator (https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement).

[10] Philippe Gruslin v Malaysia (I) (ICSID Case No. ARB/94/1); Philippe Gruslin v Malaysia (II) (ICSID Case No. ARB/99/3).

[11] At the time of publication, data for 1 August 2023 to 31 December 2023 was not yet available on UNCTAD.

[12] ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1.

[13] See footnote 13 (ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1).

[14] See footnote 13 (ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1).

[15] Barrick (PD) Australia Pty Limited v Independent State of Papua New Guinea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/27); Prairie Mining Limited v Republic of Poland (2020); Fengzhen Min v Republic of Korea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/26); Wang Jing, Li Fengju, Ren Jinglin and others v Republic of Ukraine (2020); Shift Energy Japan KK v Japan (2020); Macro Trading Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/22); Mitsui & Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/47); Patel Engineering Limited v The Republic of Mozambique (PCA Case No. 2020-21); Gokul Das Binani and Madhu Binani v Republic of North Macedonia (II) (2020); Metroplex Berhad v The Republic of the Philippines (PCA Case No. 2020-30); Maxis Communications Berhad and Global Communications Services Holdings Limited v India (2020); Goh Chin Soon v People’s Republic of China (formerly ICSID Case No. ARB/20/34)(PCA Case No. 2021-30); AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1); Akfel Commodities Pte Ltd and I-Systems Global BV v Republic of Turkey (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/36); DWS Star Bridge LLC v Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2020).

[16] Macro Trading Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/22); Goh Chin Soon v People’s Republic of China (formerly ICSID Case No. ARB/20/34) (PCA Case No. 2021-30); AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1).

[17] The World Bank ‘Foreign direct investment, net outflows (BoP, current US$)’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BM.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?end=2022&most_recent_value_desc=false&start=2022&view=bar.

[18] OECD ‘Foreign Direct Investment Statistic: Data, Analysis and Forecasts’. https://www.oecd.org/investment/statistics.htm#:~:text=The%20top%20sources%20of%20FDI,China%20(USD%2053%20billion).

[19] Including a claim brought by a dual Singapore and Dutch Investor: see Akfel Commodities Pte Ltd and I-Systems Global BV v Republic of Turkey (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/36).

[20] Including a claim brought by a dual Australia-United Kingdom national: see Mohammed Munshi v Mongolia and a claim brought by an Australia-United Kingdom company: see Churchill Mining and Planet Mining Pty Ltd v Republic of Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/40 and 12/14).

[21] PowerChina HuaDong Engineering Corporation and China Railway 18th Bureau Group Company Ltd v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/22/7); PowerChina HuaDong Engineering Corporation and China Railway 18th Bureau Group Company Ltd v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (II) (ICSID Case No. ADM/23/1).

[22] Ping An Life Insurance Company of China, Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Limited v Kingdom of Belgium (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/29).

[23] Qiong Ye and Jianping Yang v Kingdom of Cambodia (ICSID Case No. ARB/21/42).

[24] MMG Limited v Democratic Republic of Congo (2018).

[25] Junefield Gold Investments Limited v Republic of Ecuador (2022).

[26] Wang Jiazhu v Republic of Finland (2021) (UNCITRAL).

[27] Beijing Everyway Traffic and Lighting Technology Company Limited v Republic of Ghana (PCA Case No. 2021-15).

[28] Jetion Solar Co Ltd and Wuxi T-Hertz Co Ltd v Hellenic Republic (2019) (UNCITRAL).

[29] Fengzhen Min v Republic of Korea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/26).

[30] Sanum Investments Limited v Lao People’s Democratic Republic (II) (ICSID Case No. ADHOC/17/1).

[31] Alpene Ltd v Republic of Malta (ICSID Case No. ARB/21/36).

[32] Jinlong Dongli Minera Internacional SA de CV v United Mexican States (2018).

[33] Beijing Shougang Mining Investment Company Ltd, China Heilongjiang International Economic & Technical Cooperative Corp, and Qinhuangdaoshi Qinlong International Industrial Co Ltd v Mongolia (PCA Case No. 2010-20).

[34] Zhongshan Fucheng Industrial Investment Co Ltd v Federal Republic of Nigeria (2018).

[35] Tza Yap Shum v Republic of Peru (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/6).

[36] PCCW Cascade (Middle East) Ltd v Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (ICSID Case No. ARB/22/20).

[37] Huawei Technologies Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Sweden (ICSID Case No. ARB/22/2).

[38] China Machinery Engineering Corporation v Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (ICSID Case No. ARB/23/8).

[39] Wang Jing, Li Fengju, Ren Jinglin and others v Republic of Ukraine (2020).

[40] Beijing Urban Construction Group Co Ltd v Republic of Yemen (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/30).

[41] Naveen Aggarwal, Neete Gupta, and Usha Industries, Inc v Bosnia and Herzegovina (PCA Case No. 2018-03); Pramod Mittal, Sangeeta Mittal, Vartika Mittal, Shristi Mittal and Divyesh Mittal v Bosnia and Herzegovina (2023) (UNCITRAL).

[42] Gokul Das Binani and Madhu Binani v Republic of North Macedonia (I) (PCA Case No. 2018-38); Gokul Das Binani and Madhu Binani v Republic of North Macedonia (II) (2020) (UNCITRAL).

[43] Ashok Sancheti v Germany (2000).

[44] Indian Metals & Ferro Alloys Ltd v Republic of Indonesia (PCA Case No. 2015-40).

[45] Simplex Projects Ltd v Libya (2018).

[46] Patel Engineering Ltd v Republic of Mauritius (PCA Case No. 2017-34).

[47] Patel Engineering Limited v The Republic of Mozambique (PCA Case No. 2020-21).

[48] Flemingo DutyFree Shop Private Limited v Republic of Poland (PCA Case No. 2014-11).

[49] Khadamat Integrated Solutions Private Limited v The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (PCA Case No. 2019-24).

[50] Ashok Sancheti v United Kingdom (2006) (UNCITRAL).

[51] Shin Dong Baig v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/18/2); DWS Star Bridge LLC v Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2020).

[52] Ansung Housing Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/25).

[53] Korea Western Power Company Limited v India (PCA Case No. 2020-06).

[54] Lee Jong Baek and Central Asian Development Corporation v Kyrgyz Republic (MCCI Case No. A-2013/08).

[55] Shinhan Engineering & Construction Co v Libya (2013).

[56] Korea National Oil Corporation, KNOC Nigerian West Oil Company Limited, and KNOC Nigerian East Oil Company Limited v Federal Republic of Nigeria (ICSID Case No. ARB/23/19).

[57] Samsung Engineering Co, Ltd v Sultanate of Oman (ICSID Case No. ARB/15/30).

[58] SK Innovation Co Ltd v Republic of Peru (2021).

[59] Samsung Engineering Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (ICSID Case No. ARB/17/43).

[60] KTurbo Inc v United States of America (2019).

[61] Emerge Gaming and Tantalum International v Egypt (ICSID Case No. ARB/18/22).

[62] Range Resources Limited v Georgia (2019).

[63] White Industries Australia Limited v The Republic of India (2010) (UNCITRAL).

[64] Churchill Mining and Planet Mining Pty Ltd v Republic of Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/40 and 12/14).

[65] Mohammed Munshi v Mongolia (2018).

[66] Tethyan Copper Company Pty Limited v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/1).

[67] Barrick (PD) Australia Pty Limited v Independent State of Papua New Guinea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/27).

[68] Prairie Mining Limited v Republic of Poland (2020) (PCA).

[69] Aura Energy Limited v Sweden (2019).

[70] Kingsgate Consolidated Ltd v The Kingdom of Thailand (PCA Case No. 2017-36).

[71] Zeph Investments Pte. Ltd. v The Commonwealth of Australia (I); Zeph Investments Pte Ltd v The Commonwealth of Australia (II) (PCA Case No. 2023-67).

[72] Goh Chin Soon v People’s Republic of China (formerly ICSID Case No. ARB/20/34)(PCA Case No. 2021-30) and AsiaPhos Limited; Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1).

[73] Cemex Asia Holdings Ltd v Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/04/3); Oleovest Pte. Ltd. v Republic of Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/26).

[74] PACC Offshore Services Holdings Ltd v United Mexican States (ICSID Case No. UNCT/18/5).

[75] Yaung Chi OO Trading Pte Ltd v Government of the Union of Myanmar (ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1).

[76] Kenon Holdings Ltd and IC Power Ltd v Republic of Peru (ICSID Case No. ARB/19/19).

[77] Surfeit Harvest Investment Holding Pte Ltd v Republic of China (Taiwan) (2017) (PCA).

[78] Akfel Commodities Pte Ltd and I-Systems Global BV v Republic of Turkey (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/36).

[79] JGC Holdings Corporation (formerly JGC Corporation) v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/15/27).

[80] Eurus Energy Holdings Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/4).

[81] Itochu Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/18/25).

[82] Mitsui & Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/47).

[83] Nissan Motor Co, Ltd v Republic of India (PCA Case No. 2017-37).

[84] Macro Trading Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/22).

[85] World bank data. See: the World Bank ‘Foreign direct investment, net outflows (BoP, current US$)’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BM.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?end=2022&most_recent_value_desc=false&start=2022&view=bar.

[86] Also taken from the Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator on the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s website.

[87] Ekran Berhad v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/11/15); Ansung Housing Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/25); Macro Trading Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/22); Goh Chin Soon v People’s Republic of China (formerly ICSID Case No. ARB/20/34) (PCA Case No. 2021-30); AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1).

[88] Cemex Asia Holdings Ltd v Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/04/3); Churchill Mining and Planet Mining Pty Ltd v Republic of Indonesia, (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/40 and 12/14); Indian Metals & Ferro Alloys Ltd v Republic of Indonesia (PCA Case No. 2015-40); Oleovest Pte Ltd v Republic of Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/26).

[89] White Industries Australia Limited v The Republic of India (2010) (UNCITRAL); Nissan Motor Co, Ltd v Republic of India (PCA Case No. 2017-37); Korea Western Power Company Limited v India (PCA Case No. 2020-06) (PCA Case No. 2020-06); Maxis Communications Berhad and Global Communications Services Holdings Limited v India (2020) (UNCITRAL).

[90] Shin Dong Baig v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/18/2); PowerChina HuaDong Engineering Corporation and China Railway 18th Bureau Group Company Ltd v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/22/7); PowerChina HuaDong Engineering Corporation and China Railway 18th Bureau Group Company Ltd v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (II) (ICSID Case No. ADM/23/1); DWS Star Bridge LLC v Socialist Republic of Vietnam (2020).

[91] JGC Holdings Corporation (formerly JGC Corporation) v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/15/27); Eurus Energy Holdings Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/4); Itochu Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/18/25); Mitsui & Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/47).

[92] See above.

[93] Sanum Investments Limited v Lao People’s Democratic Republic (II) (ICSID Case No. ADHOC/17/1); Sanum Investments v Lao People’s Democratic Republic (I) (PCA Case No. 2013-13); Byrich Holdings Limited v Laos (2022).

[94] Philip Morris Asia Limited v The Commonwealth of Australia (PCA Case No. 2012-12); Zeph Investments Pte Ltd v The Commonwealth of Australia (I); (II) Zeph Investments Pte Ltd v The Commonwealth of Australia (II) (PCA Case No. 2023-67).

[95] Fengzhen Min v Republic of Korea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/26); Berjaya Land Berhad v Republic of Korea.

[96] Beijing Shougang Mining Investment Company Ltd, China Heilongjiang International Economic & Technical Cooperative Corp, and Qinhuangdaoshi Qinlong International Industrial Co Ltd v Mongolia (PCA Case No. 2010-20); Mohammed Munshi v Mongolia (2018).

[97] Qiong Ye and Jianping Yang v Kingdom of Cambodia (ICSID Case No. ARB/21/42).

[98] Shift Energy Japan KK v Japan (2020) (ICSID).

[99] Lee Jong Baek and Central Asian Development Corporation v Kyrgyz Republic (MCCI Case No. A- 2013/08)

[100] Yaung Chi OO Trading Pte Ltd v Government of the Union of Myanmar (ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1).

[101] Tethyan Copper Company Pty Limited v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/1).

[102] Barrick (PD) Australia Pty Limited v Independent State of Papua New Guinea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/27).

[103] Metroplex Berhad v The Republic of the Philippines (PCA Case No. 2020-30).

[104] KLS Energy Lanka Sdn. Bhd v Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (ICSID Case No. ARB/18/39).

[105] Surfeit Harvest Investment Holding Pte Ltd v Republic of China (Taiwan).

[106] Kingsgate Consolidated Ltd v The Kingdom of Thailand (PCA Case No. 2017-36).

[107] T Dymond, C Sim, L Wong, ‘The state of play of investment treaty arbitration in the Asia-Pacific’ (GAR, 2023).

[108] T Dymond, C Sim, L Wong, ‘The state of play of investment treaty arbitration in the Asia-Pacific’ (GAR, 2023), pp. 53.

[109] United Nations Population Fund, ‘Asia and the Pacific: Population trends’ (11 February 2022): https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/populationtrends

[110] World Economics, ‘Asia-Pacific’ https://www.worldeconomics.com/Regions/Asia-Pacific/.

[111]JGC Holdings Corporation (formerly JGC Corporation) v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/15/27); Eurus Energy Holdings Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/4); Mohammed Munshi v Mongolia, Itochu Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/18/25); Range Resources Limited v Georgia, Mitsui & Co, Ltd v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/47); Aura Energy Limited v Sweden (2019)

[112] Institutional Energy Charter ‘Statistics of ECT Cases as of 1/11/2023’. https://www.energychartertreaty.org/cases/statistics/.

[113] Institutional Energy Charter ‘Contracting Parties and Signatories of the Energy Charter Treaty’; https://www.energychartertreaty.org/treaty/contracting-parties-and-signatories/; European Parliamentary Research Service ‘EU Withdrawal from the Energy Charter Treaty’ (4 December 2023). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2023)754632.

[114] Gov.UK ‘UK departs Energy Charter Treaty’ https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-departs-energy- charter-treaty.

[115] Sanum Investments Limited v Lao People’s Democratic Republic (II) (ICSID Case No. ADHOC/17/1); Sanum Investments v Lao People’s Democratic Republic (I) (PCA Case No. 2013-13); Byrich Holdings Limited v Laos (2022).

[116] Goh Chin Soon v People’s Republic of China (formerly ICSID Case No. ARB/20/34)(PCA Case No. 2021-30); AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1).

[117] Yaung Chi OO Trading Pte Ltd v Government of the Union of Myanmar (ASEAN I.D. Case No. ARB/01/1); Cemex Asia Holdings Ltd v Indonesia (ICSID Case No. ARB/04/3).

[118] Gokul Das Binani and Madhu Binani v Republic of North Macedonia (I) (PCA Case No. 2018-38); Gokul Das Binani and Madhu Binani v Republic of North Macedonia (II) (2020) (UNCITRAL).

[119] Naveen Aggarwal, Neete Gupta, and Usha Industries, Inc v Bosnia and Herzegovina (PCA Case No. 2018-03); Pramod Mittal, Sangeeta Mittal, Vartika Mittal, Shristi Mittal and Divyesh Mittal v Bosnia and Herzegovina (2023) (UNCITRAL).

[120] Ansung Housing Co, Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/25); Fengzhen Min v Republic of Korea (ICSID Case No. ARB/20/26).

[121] Qiong Ye and Jianping Yang v Kingdom of Cambodia (ICSID Case No. ARB/21/42); PowerChina HuaDong Engineering Corporation and China Railway 18th Bureau Group Company Ltd v Socialist Republic of Viet Nam (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/22/7).

[122] MTD Equity Sdn. Bhd and MTD Chile SA v Chile (ICSID Case No. ARB/01/7).

[123] Kenon Holdings Ltd and IC Power Ltd v Republic of Peru (ICSID Case No. ARB/19/19).

[124] Ping An Life Insurance Company of China, Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Limited v Kingdom of Belgium (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/29).

[125] AsiaPhos Limited and Norwest Chemicals Pte Ltd v People’s Republic of China (ICSID Case No. ADM/21/1).

[126] White Industries Australia Limited v The Republic of India (2010) (UNCITRAL).

[127] Eurus Energy Holdings Corporation v Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/16/4).

[128] White Industries Australia Limited v The Republic of India (2010) (UNCITRAL), Tethyan Copper Company Pty Limited v Islamic Republic of Pakistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/1); Beijing Urban Construction Group Co Ltd v Republic of Yemen (ICSID Case No. ARB/14/30).

[129] Claudia T Salomon & Sandra Friedrich, ‘Investment in East Asia and in the Pacific’ 16 J World InvTrade 800, 808 and Chart B.1 (2015).

[130] Quebec Investment Fund Lodges CPTPP Claim Against Mexico https://www.iareporter.com/articles/quebec-investment-fund-lodges-cptpp-claim-against-mexico/.